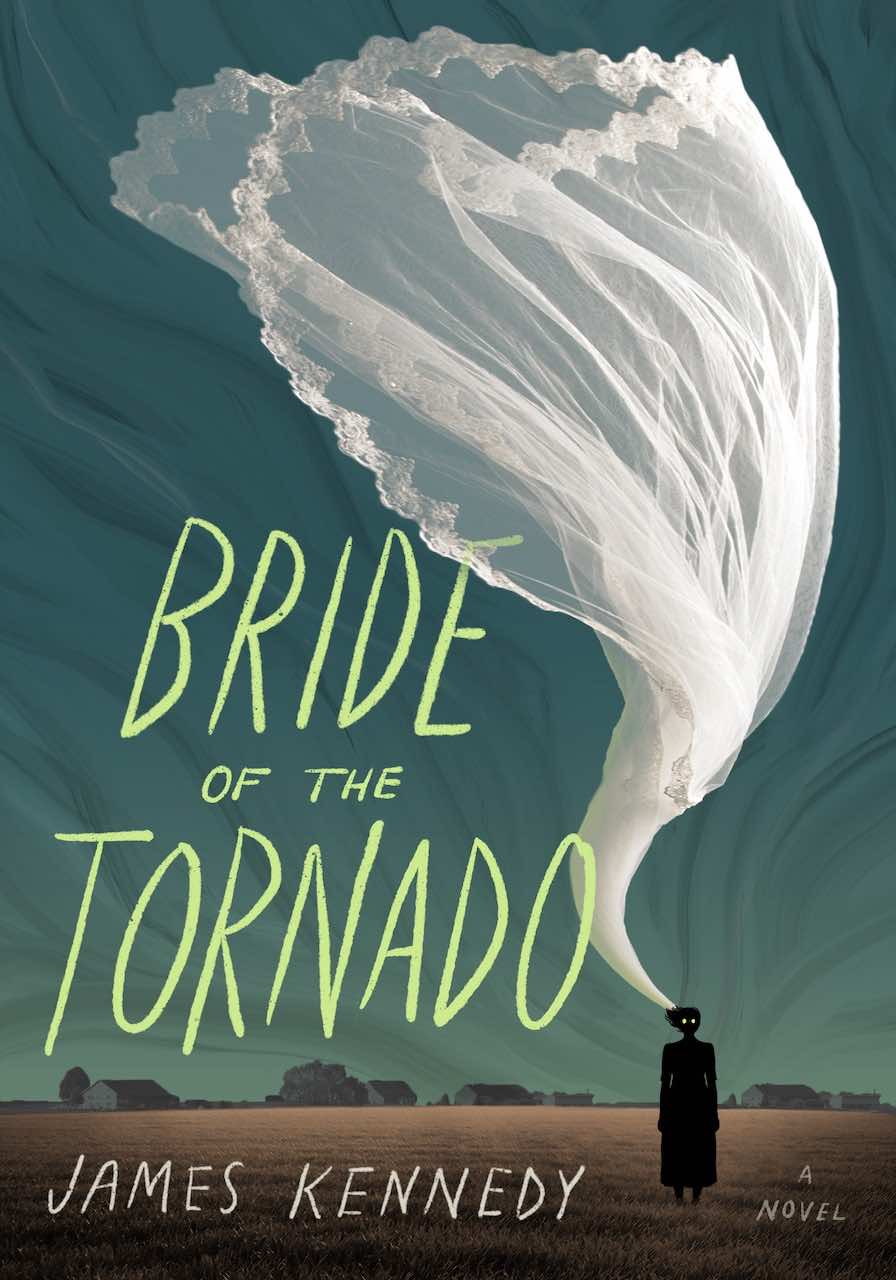

My Long Twilight Struggle With Matt Bird on the Secrets of Story Podcast

October 30, 2019

« 90-Second Newberys from our summer workshop in Hinsdale, IL! Screening dates for the NINTH ANNUAL 90-Second Newbery Film Festival, 2020! (Plus: A D&D-style movie of The Black Cauldron) »

|

I co-host a podcast about storytelling with my friend Matt Bird. It’s called The Secrets of Story and it’s a companion to Matt’s book and blog of the same name.

Matt’s a great guy! But there’s no getting around it: he is the Moriarty to my Holmes, the Goldfinger to my Bond, the Khan to my Kirk, the Newman to my Seinfeld. Neither of us can survive while the other one lives! And so, as you might expect, I object to some of the storytelling advice of my nemesis.

On our podcast, Matt usually offers some screenwriting/novel-writing wisdom and I’ll disagree with it, or challenge one of the platitudes of writing advice you hear from others (you know—books like Blake Snyder’s Save the Cat, Robert McKee’s Story, etc.). Such guidance often sounds so reasonable, illuminating, even inspiring . . . and yet I’ve found that, by taking them seriously, I’ve become snared in mental traps that drain my creativity and send me into blind alleys. Don’t get me wrong: I’ve found some useful ideas in such books, and Matt’s book is hands-down the best such book I’ve read. You should buy it! It’s good!

Even still . . . while I find the analysis in these books interesting, they derail me when I’m actually trying to create something fresh. For me, a truly new, exciting idea is always going to feel wrong at first. It’s going to break some rule. Otherwise it wouldn’t be new, right? (And only bad people love rules and checklists.)

Anyway, whenever Matt and I record an episode, I usually post about it here on the blog . . . but I just realized I haven’t posted about the last four episodes we’ve recorded! So this’ll be a long post featuring those four podcast episodes. They’re all good episodes! You should listen to them!

Let’s start with Episode 9, “Positive Passivity”:

|

You always hear the advice, “Don’t have a passive main character! The hero of your story should always be active, pushing every scene forward, constantly making big decisions that affect the world around them!” And I guess that’s true . . . or is it?

Admit it: some of the most famous characters from some of the most beloved stories are pretty passive! Consider Harry Potter, James from James and the Giant Peach, Chihiro from Spirited Away, Bella in Twilight, Charlie in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, Meg in A Wrinkle in Time, Arthur Dent in The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Alice in Alice in Wonderland, or many others. These great characters are absolutely not taking the bull by the horns in every scene. In fact, I argue in this episode, these characters are passive by design. Their stories wouldn’t work as well if they were the active, ass-kicking, empowered heroes that misguided storytelling orthodoxy demands. A hero with too much agency is, in fact, alienating! I argue that the hero can be plenty passive at the beginning of the story, as long as their agency increases throughout the story. Indeed there is something appealing about certain kinds of passivity! Matt disagrees at the beginning of the episode, but in the end I bring him around. That’s why this episode, Episode 9, is called “Positive Passivity”, and you can listen to it here:

In the comments section, commenter “Harvey Jerkwater” made this good point:

All of the stories you mentioned—Harry Potter, Spirited Away, Twilight, Alien—they’re about characters being thrown into radically strange worlds or having their regular world radically tipped by strangeness. I think that’s critical to the idea of positive passivity.

Partially this allows the worldbuilding space to happen. We see this Bold New Circumstance through the eyes of someone taking it in. You can’t start mucking with the world until we know what the world is.

Also, the protagonist suddenly taking action and making big choices when he or she has just been hurled into bizarre circumstances would make the hero look overconfident at best, and more likely a buffoon.

If the story is set in a world that’s quickly understood by the reader— e.g., “it’s a diner in rural New York State” or “it’s a temp agency in Liverpool”—then passivity is a storytelling flaw, because we don’t need to be shown that world in excruciating detail to understand its rules. We expect the protagonist also knows its rules and has no reason to be passive while he or she gets the lay of the land.

Passivity in a protagonist is fine if the story has other motors to keep the reader going. Protagonist action is a great engine, but it’s not the only one. However, other motors burn out a lot faster and tend to be more fragile.

Great point, Harvey!

Okay, on to the next episode! Back on Episode 5, Matt and I had author Jonathan Auxier as a guest. Here in Episode 10, Jonathan Auxier returns to the podcast to comment on our last three episodes . . . not only about “positive passivity,” but also my theory about the decline of the hero and the suppressed/hidden side/back half of the Hero’s Journey (Episode Eight, “The Jedi In Decline”), and also my thoughts about the application of OODA loops to storytelling (Episode Seven, “Expectations and OODA Loops”). Jonathan’s comments deepen and enrich those previous three episodes, so it’s probably best to actually listen to those episodes before you listen to Episode 10: More Fun With Jonathan Auxier:

After you’ve listened to this one, I think it’s worth it to look at Matt’s post about it, in which he has some interesting follow-up thoughts.

And now on to Episode 11: Heroic Self-Interest with Geoff Betts. Hoo boy. This is the one in which Matt and I go for each other’s throats.

Special guest Geoff Betts—Matt’s best friend from the old days—joins us to talk about the role of self-interest in characters. Matt has a piece of advice that I think that is totally wrongheaded, reductive, and depressing, which he summed up in his blog post Rule #42: People Only Want What They Want. Basically, Matt claims that characters are only really believable when they’re acting in their own self-interest. I think this is ludicrous, and that it doesn’t cover the full range of human motivation. Geoff happens to be a union organizer, and he brings his own real-world perspective in how to motivate people through self-interest. He also provides a calming influence as Matt and I get more and more furious with each other . . . as the episode goes on, I feel Matt continually redefines “self-interest” is broader and more tortured ways so that it seems to pretty much covers every case.

Anyway, come for the debate, and stay for my idea about a gender-flipped, age-flipped version of Annie, in which Annie is “Andy” (a 35-year-old Will-Ferrell-in-Elf-ish orphan), Daddy Warbucks is a Jojo-Siwa-esque instagrammer and influencer, and Grace is a take-no-crap J.K. Simmons type:

After you listen to the episode, head down to the comments section for some spirited debate. As commentor “Vlad” says, “Usually I think that Matt’s principles have some core insight going for them, and that James’ counter-examples are chipping away at the edges to refine the principle; but in this case, James is 100% right.” In your face, Bird!

That brings us to the final episode I want to feature today, Episode 12: Hollywoodization.

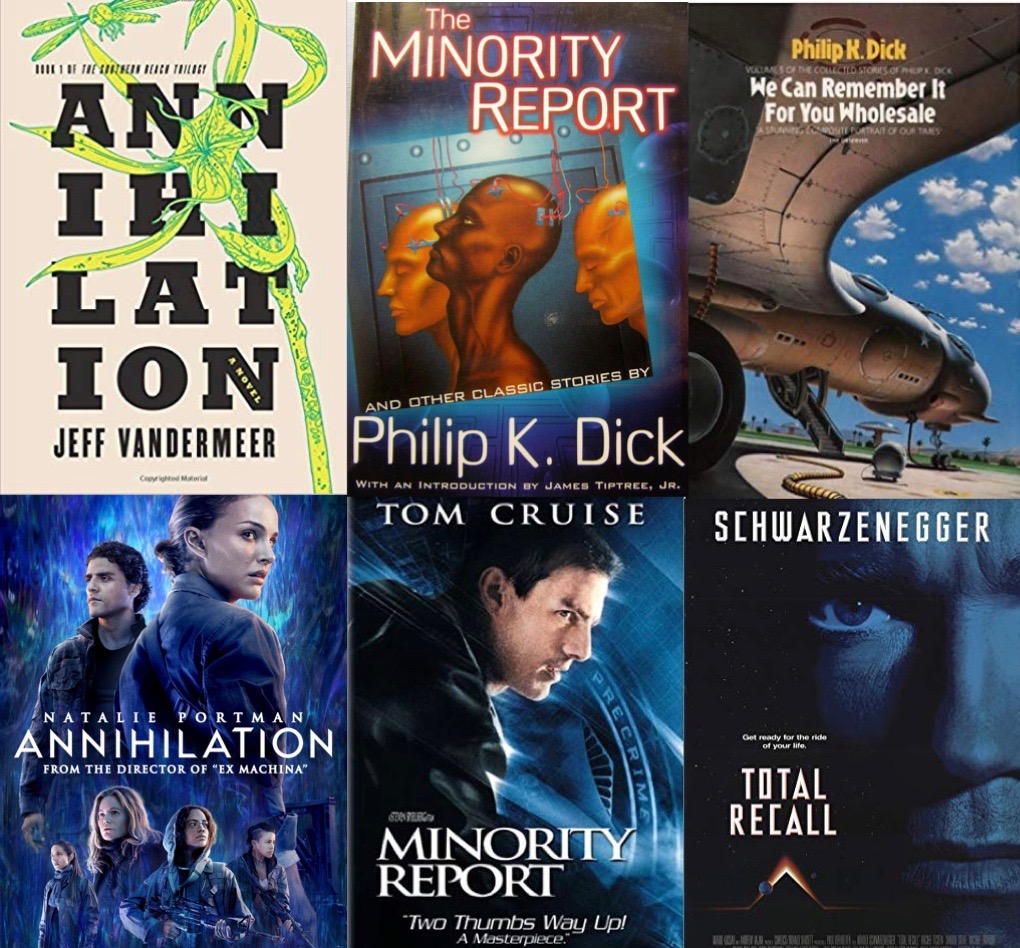

|

In this episode, we talk about the book-to-movie adaptations of Jeff Van Der Meer’s Annihilation, Philip K. Dick’s Minority Report, and Philip K. Dick’s We Can Remember It For You Wholesale (which was made into the movie Total Recall). Matt and I agree that Annihilation doesn’t fully succeed, we completely disagree about Minority Report (I loved it, he hated it), and we agree again about the bulletproof gloriousness of the 1990 Schwarezenegger version of Total Recall. Listen here:

In this episode, Matt cut much from our discussion of Annihilation. One of the things I meant to mention was that I feel that one of the elements horror movies often need to succeed is to have a “Game Over, Man!” person who is the audience surrogate for fear.

One of the reasons that Annihilation (the movie) didn’t work so well for me was that every character was so infuriatingly calm! The Gina Rodriguez character Anya came closest to being visceral and real, but all the other characters were just so professional or chilly or abstracted that there was no place for the audience’s reptile impulses to go.

In many horror movies (especially ensemble pieces), there needs to be a character who just up and says “This is nuts! What are we even doing here?” early on, and/or who acts as the audience’s lowest impulses (cowardice, lust, fear, appetite, whatever) that can ground the story.

In Aliens it’s Bill Paxton’s Hudson character who loudly proclaims his exasperation and cowardice: “Well that’s just great! That’s just great man! . . . That’s it man, game over man, game over!”

In Alien, Yaphet Kotto’s character Parker serves that role. In this year’s Midsommar, Will Poulter’s character Mark plays that role (he’s the horny jerky grad student friend who pees on the sacred tree) – he’s the most cowardly, the most directed by his base impulses. But we need that person as a release for the audience, somebody whom the audience could look at and say: “Well, if I were in that situation, maybe I wouldn’t be the bravest or cleverest person in the world, but I wouldn’t be as bad as that guy.”

That crucial “Game Over, Man!” person doesn’t exist in Annihilation– all the ladies on the team are such competent professionals, and so therefore we can’t help but feel a little distant from their adventures. Annihilation is, at least on some level, a horror movie–but horror is a primal emotion, so we need other primal emotions stoked too, or at least acknowledged, because they’re all stickily and messily and inextricably kludged together. Annihilation tries to be a POLITE, ARTY horror movie . . . and even though on balance I did enjoy it, it was not as successful as it could have been because base desires/emotions/thoughts were not given proper outlet.

And that’s that! Four podcast episodes. Four spirited arguments. If you liked these episodes, I recommend you listen to them all! After all, there are only twelve of them! And seriously, Matt’s book is good (even taking into account my disagreements). Do yourself a favor and buy it.