Interview With Someone Who Hated Odd-Fish

December 29, 2009

« Odd-Fish Art Update #3 Odd-Fish Art Update #4 »

|

This past August The Order of Odd-Fish received its first truly scathing review. Before that I’d received either ecstatic reviews, or lukewarm reviews, or okay-but-not-my-cup-of-tea reviews. Now here was someone who really ripped into the book, with a passion that made me feel like I’d personally betrayed her. Her name is Ri, and the review is here.

In the review, Ri admitted that she didn’t actually finish the book. Intrigued, I got in contact with her. She decided to finish the book and re-review it.

She still didn’t like it.

You read a lot of interviews in which the author is asked questions by a fan. I thought, wouldn’t it be more interesting to do an interview in which the interviewer totally hates your book? Ri was game, and thus the following interview was born.

Warning: this interview is long and detailed, and thus it ain’t for everybody, just the sexy people.

|

Ri: What’s up with Ian’s mustache? That thing made me want to scream. Usually, books do not make me that angry . . . Has anyone else voiced complaints against it? Did Ian shave it off because Audrey and Jo’s campaign worked, or because he wanted Jo to like him more? How old is Ian, anyway? When he’s older, will he grow it back?

James: For those of you who haven’t read Odd-Fish, Jo is the heroine and Ian is a boy her age. When we first meet Ian, he is described as having “the wispy beginnings of a mustache, which did not suit him.”

To get the full effect of Ri’s distaste for the mustache, I must quote her review at length:

Oh God. Ian’s mustache. That thing bugged the freakin’ hell outta me. No joke. In fact, it annoyed me so much that I kept track of how many times it was mentioned. The grand total was 10 times before Ian (thank God) finally shaved the damn thing off.

Remember before, how I had said that if you want me to like a character, don’t keep reminding me that there is something abhorrent about them? Yeah. Well, fail. Maybe Kennedy just didn’t know that. Perhaps he hasn’t read enough romances. But if you don’t know romance, don’t write it (a warning to all you Stephanie Meyer wannabes)!

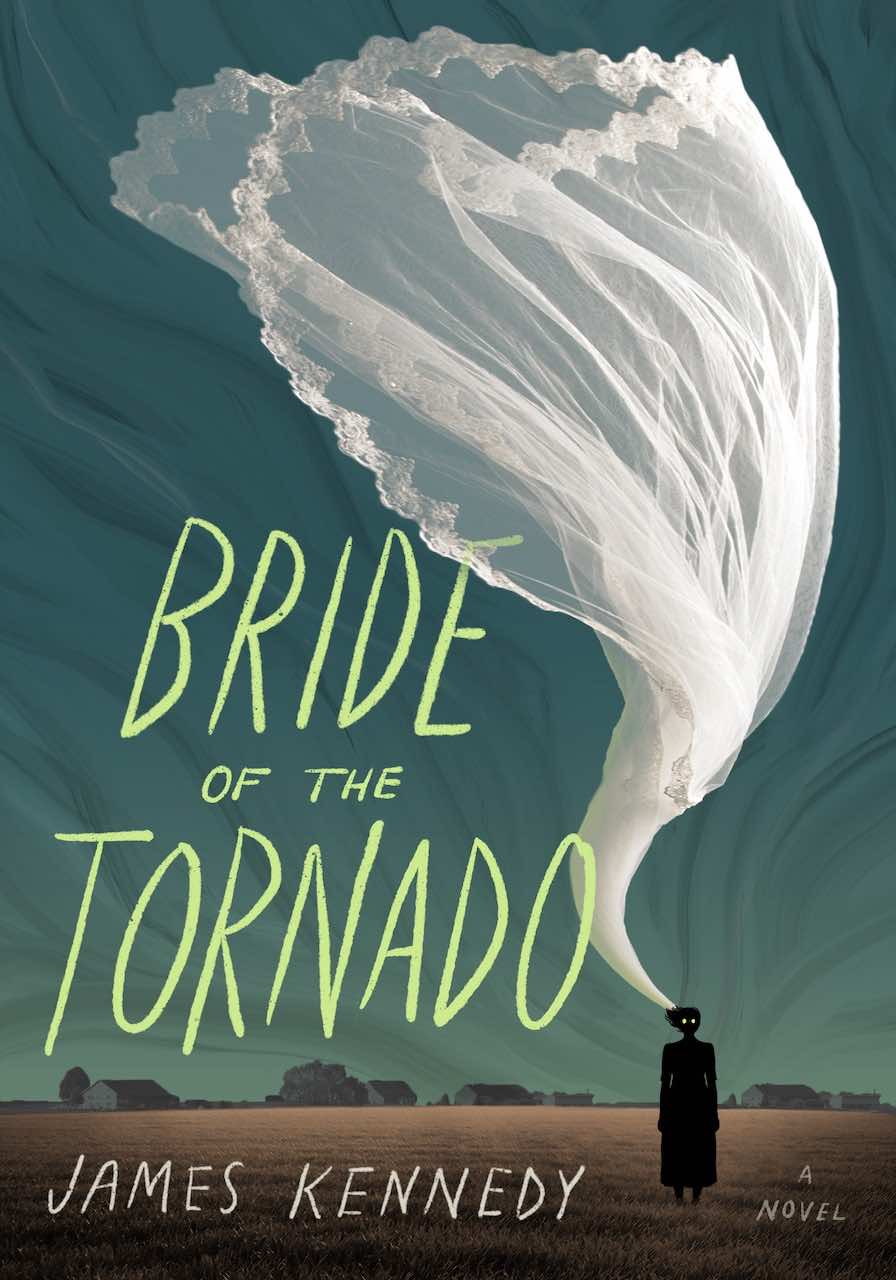

“Abhorrent”? Why all the mustache hate? After all, you can’t properly impersonate a rogue generalissimo without one:

|

|

I could post attractive pictures of myself with a mustache all day.

You’re right, I don’t read much romance. But I was deliberately writing against that template. None of my own relationships have been like the romances you read about in books. Jo and Ian’s relationship feels more real to me. They’re still figuring themselves out.

They’re attracted to each other in a confused way, yes, but they’re also friends. They rely on each other, they routinely hang out, and they feel at ease with each other. But they also get on each other’s nerves. Even after Jo fumblingly kisses Ian—and Jo surprises herself just as much as she surprises Ian—they still can’t figure out how they feel about each other. I wanted to catch that adolescent confusion, that awkward ambiguity.

You mentioned Stephanie Meyer, so I’ll put this in terms of Twilight. I didn’t want Ian to be an Edward Cullen who is repeatedly (and vacuously) described as “perfect.” As I’m sure you know, Edwards only exist in girls’ imaginations. Most boys are more like Ian. Why do you think Edward is played by a 22-year-old in the movie?

I used the mustache as a physical shorthand for Ian’s awkward transition to manhood. Ian wants to be grown-up, knowledgeable, and dependable. But he can’t quite carry it off yet, just like he can’t quite carry off the mustache.

The mustache causes everyone to show character. Ian keeps the mustache for a long time, even in the teeth of everyone teasing him—which shows he’s not concerned with what others think. Jo doesn’t care about Ian’s mustache unless Audrey is egging her on. That shows physical looks don’t really matter that much to Jo. As for Audrey, she just uses the mustache as an excuse to indulge in Audrey-esque pranks and taunts.

I think at a certain point in adolescence people are vain about their looks, but utterly clueless about aesthetics and obstinate in their fashion mistakes. Ian, like Jo, is in an awkward stage of growing up. It’s a fragile, weird, interesting time. Ian’s gauche mustache is a perfect emblem of that.

In fact, now that I’ve answered your question, I’ve convinced myself that Ian’s mustache is, far from an error, a masterstroke. Bravo, me!

|

Why the Belgian Prankster? As I mentioned before, it does not sound particularly evil and I could only ever think of him as a TV show star. Why not go with Nils or Sir Nils, if you really want to get crazy?

You want love interests to be handsome. You want villains to sound evil. I think that that path leads to obvious choices, and finally boring stories. Do we really need another “Dark Lord,” another “Xultar the Emperor Overzorp of Deathdoom”?

I didn’t want people to know how to feel about the Belgian Prankster at first. Is he supposed to be funny? Vaguely unsettling? Outright demonic? Even though the overall structure of Odd-Fish is traditional, I wanted each episode and detail to feel fresh, to have the tang of the arbitrary, even at the risk of being disorienting the first time you read it.

Here’s why he’s called the Belgian Prankster. In 1998 a Belgian named Noel Godin smashed a pie in Bill Gates’ face in the street. It was supposed to be a kind of performance art.

Interestingly, all the newspapers or reporters invariably referred to him as “Belgian prankster Noel Godin” or just “a Belgian prankster.” I found the phrase Belgian Prankster irresistible. It had a sinister lilt for me. I thought, what if this Belgian Prankster graduated from mere pie-throwing to more insane, dangerous, and finally supernatural stunts? Like filling the Grand Canyon with pistachio pudding? Or turning the Eiffel Tower upside-down? A celebrity terrorist—as if Osama bin Laden had his own whimsical reality show—a man in pursuit of the worst practical joke, the most apocalyptic prank.

The “Belgian” part makes it feel off-kilter, makes it bracingly arbitrary. So when my Belgian Prankster starts doing truly hideous things, there is a certain queasiness because it’s just a goofy name, not something thuddingly obvious like “Zuulgrokker the Unholy Skullcrapper.”

And “Prankster” puts him in the tradition of supervillains specializing in absurd nihilism like Batman’s Joker or Watchmen’s Comedian.

|

|

To my mind, “Sir Nils” doesn’t come close in richness. Although I do suggest the nihilism behind his character by choosing the name “Nils,” a variant of “nil”—“Sir Nothing.”

On the subject of Sir Nils, was there more of a history behind him? How did he get mixed up with the Silent Sisters, exactly?

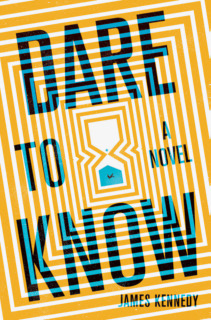

There is more history behind him, but I won’t reveal it here. I have two sequels to Odd-Fish planned as well as a prequel!

And on the subject of the Silent Sisters, was Jo’s mom tight with them or did she just randomly get chosen (I was really confused about this; I think I might have skipped a page or something . . . )?

Jo’s mother’s specialty for the Odd-Fish was obscure cults. She had gone undercover in the Silent Sisters to research her article for the Appendix, and gotten in over her head. The pages you skipped are page 282 and page 286.

I was interested with Ken Kiang during the beginning and his background was interesting, but towards the end, I was skimming his scenes. Was I just not picking up on the subtle action?

Ken Kiang is a comic character. He starts out as the villain of the book, but somewhere along the way, he gets demoted. The Belgian Prankster replaces him as villain. This sets Ken Kiang off on a journey to figure out who he is.

Ken Kiang’s story is a comedic mirror-image of Jo’s story. Jo is an innocent girl who nevertheless has a implacable evil deep inside her. She tries to fight it and finally succeeds. Ken Kiang is the opposite: he desperately wants to be evil but he just can’t pull it off. Humiliatingly, he is doomed to be good. Ken Kiang’s story is the reverse of Jo’s, its comic counterpoint.

You’re very kind to attribute your lack of interest to “not picking up on subtle action.” I don’t think I’ve ever been accused of subtlety before.

Why didn’t you kill Ken Kiang heroically? Was he just the sort of character to live?

Ken Kiang is too silly to die heroically. And Ken Kiang’s way of looking at the world is quintessentially Oddfishian. It only makes sense for him to become a knight of the Odd-Fish at the end.

Also, I’m not a punitive writer. I don’t like “punishing” characters who are “evil.”

Why even have Ken Kiang in there? When it comes down to it, he didn’t have that much of a role to play.

There were times, in early drafts, when I experimented with removing Ken Kiang. It never worked. I found that his removal drained too much comic life and insouciant absurdity from the story. His story is a ludicrous reversal of Jo’s, and the counterpoint breathes fresh air into what could have easily turned into a mere genre exercise.

When the Belgian Prankster replaces Ken Kiang as the villain, this scrambles the reader’s expectations. As I was writing Odd-Fish, my first priority was to make it unpredictable. I even wanted the reader to throw down occasionally the book and yell, “What is Kennedy giving me now?” But on finishing it, I wanted the reader to feel, “It was all inevitable; it couldn’t have happened any other way.” Moment-by-moment, keep the reader unbalanced; overall, satisfy the most traditional structural norms.

Also, once the Ken Kiang piece was put on the chessboard, I could use him to solve technical storytelling problems. For instance, I didn’t have to write the obligatory scene where Aunt Lily tells Jo about her fateful backstory. This is a common scene in fantasy: the story grinds to a halt while a mentor gives a long-winded explanation to the hero. I solved this by having the Belgian Prankster explain it to Ken Kiang instead. Ken Kiang doesn’t really care and thus can react much more naturally (for him, the scene is all about finding a way to kill the Belgian Prankster). I’m free to cut to Jo’s reaction after all the heavy lifting of exposition is done.

Another advantage: the Eldritch City we see through Ken Kiang is different than the Eldritch City we experience through Jo. Having more than one point of view of the city gives it depth.

Heck, why even have the Belgian Prankster? You could have made Ian the vessel of the Silent Sisters and then both he and Jo would have been wicked. But Ian could have been in denial and confronted Jo about her Ichthala-ness, and then there would have been some real drama when he couldn’t suppress his powers anymore and Jo found out the truth. I don’t think apology guns would cut it for that . . .

That would be a completely different book.

I said in my review that I thought this book would have been better if Jo wasn’t a dangerous baby at all, just a girl brought into the Order from the outside. Did you ever consider writing the story like this? If you did, why didn’t you go with it?

I think the apocalyptic subplot gives a sharper urgency to Jo’s experience of Eldritch City. I haven’t seen this particular plot done. It felt original to me. To put it in context, it’s almost a complete reversal of Harry Potter. Harry is a beloved celebrity in the wizarding world (at least at first). Jo, on the other hand, would be lynched if people found out she was in Eldritch City.

Harry Potter is the boy who lived; Jo Hazelwood is the girl who kills.

It seemed like a fertile reversal of the “Chosen One” archetype. What if, instead of being the one “chosen” to save the universe—something we’ve seen a million times—you were “chosen” to destroy it?

That’s why it was also essential for Eldritch City to be a fun, fascinating, lovable place. It’s much more wrenching if the place you’re destined to destroy is a place you’ve come to cherish.

The tension of Jo’s secret gives emotional pungency to scenes that would’ve otherwise been routine. And, in a way, I have done what you suggested. Jo is a normal girl brought in from the outside. She triumphs not through mastery of superpowers, but through her ordinariness. Jo walks away from her “Chosen One” destiny and refuses her supernatural abilities. She ends her story not exalted in some otherworldly pantheon, but eating at a table with her friends. After all the madcap absurdity, after all the nightmarish trials, Jo achieves becoming an ordinary person.

Why did you choose to go with the action/adventure/intrigue plot as opposed to the story where not much happens but big things are achieved? Or a Jo’s-Adventures / Romantic Comedy-thing?

Uh, I’m not sure what you mean when you talk about a story “where not much happens but big things are achieved.” How would that be preferable to “action / adventure / intrigue”?

I actually have to say, I kinda liked the whole Silent Sister thing with the All-Devouring Mother. The story behind the gods was pretty interesting. Did you make that all up?

I did indeed make it up. I’ll give a brief explanation of where it came from.

Jo is a female hero, so I wanted the villain to be female too. For instance, in Star Wars the hero is a boy, Luke Skywalker. The villain is Darth Vader, or “dark father.”

My heroine is a girl. So what would a “dark mother” be like?

There’s a Hindu goddess associated with death and destruction called Kali. I took that as a partial inspiration: “What if something like Kali walked among us?” I was also really into the Alien movies growing up, and in particular, the scene at the end of Aliens when Ripley fights the huge disgusting mother alien. Those images burned into my subconscious.

|

|

The dark side of the nurturing mothering instinct is smothering. What is the ultimate smothering? Devouring. (That’s why the theme of eating, of digestion, runs throughout the book.) So my goddess is the ultimate mouth—the “All-Devouring Mother.” It wants to gobble up the universe for its own good, to harmonize its discord, to keep it “safe.” The idea was getting richer.

I like stories in which the hero has a special intimacy with the villain. So I decided that the All-Devouring Mother wouldn’t be something outside of Jo that she fights against. It would be more interesting that she secretly was the All-Devouring Mother, and she had to find a way to thwart the terrible prophecies about her. When Jo confronts her true nature, she loses everything—even her status as a “hero.” She isn’t the savior of Eldritch City, but the monster that Eldritch City must be protected against. She is a walking apocalypse.

And that brings us to the Silent Sisters. A certain dark corner of human psychology has a cosmic death wish, is in love with the end of the world. In a tragic way, you see this in suicide bombers; in a farcical way, you see it in apocalypse porn like those putrid Left Behind books. In this way of thinking, Armageddon is not a disastrous cataclysm but a blissful cleansing, a reconciling to the divine. I thought, what if there was a doomsday cult dedicated to this world-destroying goddess? That’s where the Silent Sisters came from.

The actual term “Silent Sisters” comes from Thomas Mann’s book The Magic Mountain, which is set in a tuberculosis sanatorium. Some thermometers in the sanatorium are called “silent sisters” because they have no markings. Why do they have no markings? Because some patients are so accustomed to their years-long confinement at the hospital that they don’t want to leave. So even after they’ve become well, they try to fake a high temperature. In that case, the doctors use an unmarked thermometer (a “silent sister”) and then measure the mercury with a ruler to find out if the patient is really sick. The behavior of these patients is like the Silent Sisters in Odd-Fish: refusing to leave their safe, predictable niches, refusing the messy, dangerous adventure of life. More on the topic here.

Now I was ready to write the origin story of the All-Devouring Mother—which I realized had to be the origin story of the universe. And this brings us into religious territory.

It’s easy to forget that much of the best-loved fantasy books are written by committed Christians. For J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, and Madeleine L’Engle, their Christianity informs and enriches the mythologies they created. Christianity is thus a hidden part of the DNA of fantasy. This is even true for Harry Potter: though never explicitly Christian, it is chock-full of Christian archetypes. It could hardly manage otherwise, since it invokes a whimsical medievalism, and it is impossible to redact Christianity from the medieval.

This is true even in reverse. Some writers get their energy from their opposition to Christianity. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials series is an explicit condemnation of Christianity, a kind of anti-Narnia. But that only confirms Christianity’s central place in the DNA of fantasy. Fantasy, at its best and deepest moments, touches ultimate questions of the universe and our place in it. But this is also the province of religion.

I felt that the very act of developing a metaphysics and an origin story for my fantasy world would bring me into this debate. And it was a debate that is very, very wearying to me. I just have no interest in it at all. I’m not interested in taking a pro-Christian or anti-Christian stance in my work. I have no axe to grind. And I felt it was a dichotomy that was aesthetically exhausted.

I solved it by not working with Western archetypes. Instead of having One True God (Lewis), or No God At All (Pullman), I decided to have 144,444 gods. Instead of transposing themes for Christianity into the realm of fantasy, like Lewis does with the crucifixion and resurrection in Narnia—and instead of crafting dark parodies of Western religious practices, such as Pullman does with the Magisterium in His Dark Materials—I instead tuned into ideas, practices, and mythologies found in Hinduism, Shinto, and Buddhism—thus escaping the whole debate.

It would be pretentious to claim I know the least thing about Hinduism, Shinto, etc. But the little contact I have had with them, through travel and reading, was enough to spark my imagination in directions that are skew to the Western tradition, freeing me from the locked categories that were invisibly guiding my imagination. The mythologies of Eldritch City are not directly inspired by any one story in those non-Western traditions, but they share a similar flavor.

DING DING! Round one is over. Back to our corners. Doc, doc, where’s my hot towels? Where’s my mouthguard? Where’s my hairspray, where’s my chronometer, where’s my sun hat?! I don’t need my sun hat . . .

|

DING DING! Round two!

You know, you could’ve gone with the Romantic Comedy and saved the Ichthala thing for another, more action-filled book . . . which reminds me. Even though I loved all the random scenes (with Chatterbox and Korsakov’s hunt for the Schwenk), why put them in there? Your book seemed to want to be too many things at once, and to be frank, they kind of seemed out of place.

So your favorite scenes are precisely the ones you want to cut? Hmmm. In that I see a glimmer of possible agreement between us. Let me see if I can talk you around.

In my mind, there’s two kinds of stories. On one hand you have sprawling, shaggy tales that are not so much read as inhabited—the reader accepts an invitation to board at a vast, creaky old house full of strange treasure, secret staircases, and hidden attics. You have to read and re-read these books to get to the bottom of them; they’re the kind of book that you can reopen anywhere and start rereading. Examples are Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast books, Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past, the Lord of the Rings books, and James Joyce’s Ulysses. In books like these, plot is often secondary, a launching-point for digressions, stories-within-stories, intertextual games, and other glorious irrelevancies. These kinds of books are frequently long, but they don’t have to be: The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy and Alice in Wonderland fit into this group, books that are less concerned with telling a story than building a world. We’ll call these “shaggy” stories. Their strength is playfulness and generosity of vision.

On the other hand, we have stories that are tight, lean, and focused. Every detail efficiently clicks into and builds upon the others, sweeping the reader forward on a thrilling ride. Off the top of my head, Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Michael Crichton’s Sphere, and S.E. Hinton’s The Outsiders fall in this category, which we’ll call “lean” stories. Their strength is page-turning, breathless pacing.

Of course there’s no such thing as a purely shaggy or purely lean story, but you see where I’m going. The Order of Odd-Fish is quite deliberately and proudly a shaggy story, and it should be judged by the norms of shagginess, not of leanness.

Indeed, the very substance of its plot is a defense of irrelevance and digression. The title refers to a group of knights whose purpose is to aimlessly fiddle about, and the great work they’re collaborating on—the Appendix—is named after precisely that part of a book, or indeed the human body, that can be safely left out. The knights study dubious, irrelevant topics, and it turns out they don’t especially care if the knowledge they collect is strictly true or not. This ethos overflows the activities of the knights and spills over into the text itself, infecting the whole book with this dithering spirit.

If the Odd-Fish knights had their way, they’d muddle along for hundreds of pages in happy irrelevance, going off on Schwenk-hunts, holding elaborate feasts, dressing up in needlessly ornate costumes. It’s the villains who are trying to impose a plot on these happy dilettantes. The Belgian Prankster and the Silent Sisters are the snakes of plot, corrupting a paradise of character and setting.

One of the important themes of my book is to praise digression, to assert the worth of aimlessness, to defend the meandering and the marginal. Since your favorite parts of the book are precisely where I gaily tell the plot to go to hell, and putter off on some goofy irrelevance, I think you understand this, and on some level, you might even agree with me.

Dugan was an interesting character, what with his being in with the mafia and all, but what was his purpose? I can’t remember him doing anything after the tournament . . . Actually, when he was first introduced, I thought there was going to be a love triangle with him and Jo and Ian. Did you ever consider that?

I did in fact consider it, but abandoned the idea since it would further complicate an already complicated story. (I admit there is, in the end, such a thing as too much complication!) Some loose tendrils of that subplot must still be flopping around. Very perceptive of you to zero in on them. I’m glad I didn’t go that route, though, because I have an idea for Dugan in the sequel(s) that’s much more interesting.

Since Aunt Lily is dead, who is Jo a squire for?

I hate to say this again, but . . . that’s another issue for the sequel(s).

Jo and Ian seemed to get off to a quick start with all that snuggling. What was up with that? Aren’t they a bit too young for that, anyways?

Really? They’re thirteen. Maybe things have changed since I was that age.

Towards the middle, the romance disappeared. One moment, Jo was making Ian jealous, and then—nothing! Where did it go? During that middle bit, they seemed to be great friends, but nothing romantic.

Jo was freaked out about Ian’s murderous attitude toward the Ichthala. Things were going swimmingly until the scene in the tapestry room, when Ian said he would kill the Ichthala (Jo) if he discovered her. Jo’s secret is the obstacle to any romance. After that scene, they’re able to become friends, but Jo holds back her full emotions because she’s also holding back her secret. Their feelings for each other are submerged, but are still bubbling under the surface, and come to a boil when Jo kisses Ian at the victory party.

This is out of nowhere, but how many husbands has Oona Looch had?

An entirely new branch of mathematics would have to be invented to answer that.

I have to say again, that I really loved Ian and Jo’s dance. Very cute. Why wasn’t there more of that?

I think it worked because there wasn’t more of that.

Insofar as that scene worked, it’s because romantic tension was building up between Jo and Ian. I wanted that tension to be subtle, hidden, and implied. If I kept hitting that note, giving the reader “more of that,” it would have turned out leaden. Faux-romantic scenes of characters exchanging long, significant looks, or of mooning about in an emo way, do not appeal to me. I wanted the romantic buildup to be indirect enough so that when Jo impulsively kisses Ian, it’s a surprise to Jo, Ian, and the reader—and yet, in retrospect, it makes perfect sense. (Why were they hanging out so much? What did happen to all that initial snuggling?) By discreetly omitting details about Jo and Ian’s attraction until that crucial moment—by allowing them the privacy of their feelings rather than heavy-handedly exposing them—I could achieve the effect you clearly appreciated, but not otherwise. In such delicate emotional waters, less is more.

This is also true in horror movies. In monster movies, rule number one is not to show the monster too much. (Alien is a masterful example of this.) Emotions become present in the reader’s mind precisely because they’re absent on the page.

J.K Rowling said she wanted to go back and redo parts of the Harry Potter books (because some of the math and junk was off). Do you feel that way, ever?

I’m certain there are logical errors in the book, but I haven’t found any yet.

For me, the characters made this book. Will there ever be another focusing just on them? (Please say yes! Just a short story collection, maybe…)

Hopefully in a sequel to Odd-Fish, I’ll strike a balance between character and plot that you’ll find more satisfying. Pace my previous remarks, there’s no such thing as character without plot. Character is revealed through plot, and plot shapes character, so I could never have a book that focuses just on characters; they need to be doing something, after all, even if it’s just frittering and dithering.

And speaking of characters, are any of them based off real life people?

Each character is, in the end, only themselves, but certain friends and acquaintances provided the initial inspiration. I plead the fifth on exactly who.

Do you wish any of them were real? I wouldn’t mind spending the afternoon with Audrey. She seemed like fun.

Audrey is a firecracker. I have spent some memorable afternoons with Audreys.

Was Odd-Fish the book you’ve always wanted to write? Dreamed about since you were a little boy? Or is there another?

There was no particular story I always wanted to write, but I always wanted to be a writer. Odd-Fish evolved piecemeal over many years. I didn’t experience a total vision of Odd-Fish one day, and then simply execute the predetermined design. The book became what it was through the process of writing it. I guess, now that I’ve written Odd-Fish, it has become the book I always wanted to write?

When I’m done with my next book, I’ll probably feel the same way about it.

I’m working on the book I’ve always wanted to write. Hopefully it will be epic. But it will not be the only book I write. My other stories all take place in the same world, but at radically different times. Will something like this be happening with Eldritch City?

That sounds like an interesting idea, and I’ve read other books that have done this successfully. (The Foundation Trilogy by Isaac Asimov, for instance.) However, I don’t see the Odd-Fish series going in that direction. With stories that take place at radically different times, you can’t watch characters evolve from book to book (unless they’re supernaturally long-lived). And character is the most important thing to me. It seems that such a series would have to be idea-driven or theme-driven rather than character-driven, and though I like to read that kind of thing, writing it wouldn’t play to my strengths.

I just looked up Eldritch. Apparently it means “weird.” I get it.

Word.

If you were an Odd-Fish knight, what would you study? I’d practice the art of Long-bottling, which is the Guyanese art of having nothing to do and all day to do it in. Quite intense stuff.

You’re going to enjoy college.

And finally, any advice for aspiring authors?

You’re asking for my writing advice even though you don’t like my . . . ? Anyway.

Don’t think about writing; just write. There are at least 500,000 words standing between you and your first glimmer of quality. You have to put in the time. You have to write thousands of sentences before you write your first good sentence. There is no substitute for parking yourself in a chair and writing. Ninety percent of what you will write, even if you’re a professional writer, will be poop. You must swim through the poop to find the diamond. There is no other way.

Thank you very much for the interview (it was long. I apologize. I just can’t seem to stop typing once I start.) Though I cannot say I enjoyed all of your book, it must be known that the parts I liked, I really liked, and it was worth reading the book for those bits.

Thank you too, Ri!

But wait . . . I see from your website . . . that even with your scathing reviews, you have classified The Order of Odd-Fish under “Books I Liked”?!?!

Could it be . . .

|