The DARE TO KNOW Playlist

|

Back in 2009 I posted a playlist for my first novel, The Order of Odd-Fish. I had a ball putting it together. Since Odd-Fish is a fantasy, it gave me the opportunity to rummage around in strange music to find songs appropriate for a fantastical world.

Music also plays a big role in my new novel Dare to Know, which is set in a world mostly like our own. Since one of its subplots concerns an eerie conspiracy theory about Top 40 pop music throughout the years, it was natural for me to create a playlist for Dare to Know too!

I chose 28 songs in all. You can browse the songs and hear snippets in the widget below, or listen to the complete songs on Spotify here.

But why did I choose these particular songs?

First, some background. A few years ago, I visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It was nice to see artifacts like Little Richard’s costumes and whatever, but what really fascinated me was the exhibit documenting the paranoid preachers and right-wing kooks who protested rock and roll in the 1950s. In the context of the museum, these sweaty weirdos seemed to me far more punk and nonconformist than Eric Clapton’s hundredth guitar, etc. They literally believed that rock and roll could drag you to hell! That’s metal.

First, some background. A few years ago, I visited the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. It was nice to see artifacts like Little Richard’s costumes and whatever, but what really fascinated me was the exhibit documenting the paranoid preachers and right-wing kooks who protested rock and roll in the 1950s. In the context of the museum, these sweaty weirdos seemed to me far more punk and nonconformist than Eric Clapton’s hundredth guitar, etc. They literally believed that rock and roll could drag you to hell! That’s metal.

I admired their nuttiness—perhaps because, when I was a kid in the 1980s, I kind of felt the same way. For me, there was something a little creepy about certain songs on the radio, especially songs from the 1960s and early 1970s.

Early on in Dare to Know, the main character and his friend Renard invent a theory about classic rock: that this oddly inescapable music is secretly the voice of “something vast and invisible and evil that permeated America,” a malign entity that expresses itself indirectly through FM radio “in spurts and starts, in disconnected phrases across songs, across decades,” a presence that would in time “do awful things to all of us.”

There are certain songs “everyone knows” whether we want to or not, the background radiation of their eras. But as time goes by, and those eras recede, the pop music that “everybody knows” begins to sound strange, stilted, or outright menacing—perhaps because those sounds were meant to be ephemeral, but now are persisting in a zombie-like way long after their time has passed. One of the themes of Dare to Know is about how repetition can have a death grip on us, about how nostalgia deforms us.

Many songs on this playlist are mentioned in Dare to Know. Other songs on this playlist aren’t actually named in the book, but they express Dare to Know’s various moods.

I juxtaposed songs in this list so we might perceive in a different way those songs that “everyone knows.” Many of us have heard Madonna’s “Into the Groove” so many times that we’re in a sense anesthetized to it. But sandwiched between Mica Levi and Mount Eerie, maybe we have a chance of hearing this tired song in a bracing way: how robotic, brittle, and thrillingly insectlike it is. Hopefully this playlist’s more cryptic and atmospheric tracks will throw the better-known tracks into relief, revealing fresh aspects.

These are all songs that have a strong effect on me. Some of these songs I love. Some of them are included to make us both suffer a little.

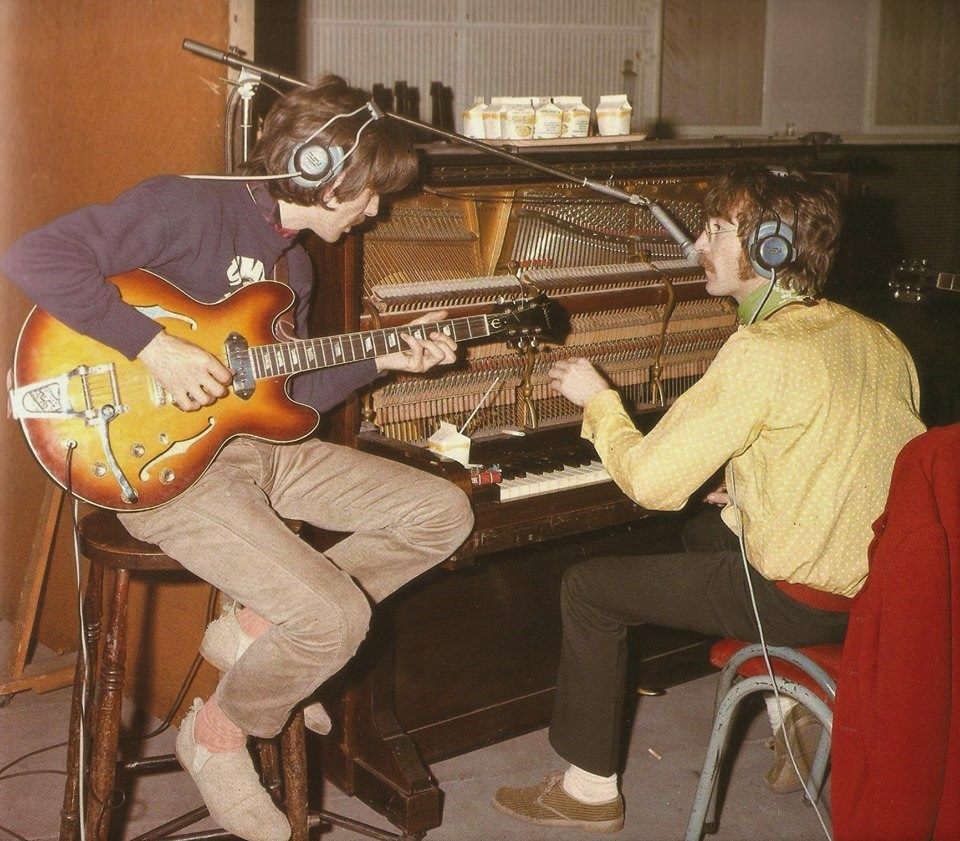

1. “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)” by The Beatles

1. “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)” by The Beatles

It’s been dismissed as a novelty song, but I believe this is the best of all Beatles songs. That’s not me being contrary—Paul McCartney himself claimed it was his favorite Beatles track. It’s definitely one of their strangest.

I didn’t hear “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)” until I was in college. It was the first Beatles song that really grabbed me and surprised me, because it sounds like a bunch of guys goofing off in a basement, similar to the shambling indie rock I liked at the time—there’s nothing elevated or canonical about it. That spoke to me more than “Eleanor Rigby.” So it’s always been a big song for me.

And yet this is also a deeply haunted song. Listening to it is like looking at a picture of a creepy old-fashioned clown. Mirth existed here once, I guess . . . but it’s just eerie now!

I write about this song quite a bit in Dare to Know, so I won’t repeat myself here. But this seemingly jokey song is fundamental to what the book is all about. I based Dare to Know’s four-part structure on this song’s oddly collapsing four-part scheme—indeed, the original title of the book was You Know My Name, Look Up The Number.

2. “The Boys of Summer” by Don Henley

2. “The Boys of Summer” by Don Henley

At a physics summer camp for junior high school students, the narrator and his roommate Renard share confessions about how they are both weirded out by certain types of radio music. For our narrator, it’s the “meandering, bearded, shaggy, bloated” songs from the late 1960s and 1970s, which puts him in the mind of drugs, dirtiness, and Charles Manson; but Renard is more unsettled by more polished, synthetic songs from the 1980s that he characterizes as “reptilian, sinister, metallic.”

Renard recalls his feelings about “The Boys of Summer,” in particular the lyric “Out on the road today, I saw a deadhead sticker on a Cadillac / A little voice inside my head said don’t look back, you can never look back”—which is much more frightening if you’re a child who doesn’t know what a “deadhead” is, and therefore you might assume it’s a devilish symbol that you must never gaze upon for some unspeakable reason.

The wistful synthesizers give this song a Stranger Things vibe, which is a fitting mood for the sections of Dare to Know that describe the narrator and Renard’s spooky teenage 1980s adventures at summer camp.

3. “Zuhura” by Slikback

3. “Zuhura” by Slikback

The discovery of subatomic particles called “thanatons” leads to a type of mathematics that can predict the exact moment of a person’s death. But this type of mathematics can’t be done by a computer—it is a “subjective math” that can only be accomplished by a human, by hand, in a surreal one-on-one interview with the person who wants to know their death-time. It’s an unnerving algorithm that feels part math problem, part nonsense poetry, part pagan ritual.

I reached out to my friend Philip Montoro, the music editor of the Chicago Reader, for help with this one. I told him I was having a hard time finding a song that puts us in the mood of the “ominous mechanical mathematical workings of the death algorithm.”

Well—Philip delivered. He chose this track by experimental producer Slikback, whom Philip describes in this blog post as “24-year-old Fredrick Mwaura Njau, born in Nairobi, Kenya, and based in Kampala, Uganda, since 2016 . . . He combines elements of trap, techno, footwork, gqom, and more.”

The song nails for me the relentless, forbidding machinations of the death equation—and it also feels like a first glimpse of the ominous heart beating underneath all the tunes in this playlist. A brief encounter with that “something vast and invisible and evil,” tracing the eerie patterns pulsing within the narrator’s life, within the music that surrounds him, and within the universe. We’ll hear from that “vast invisible thing” again a few more times in this playlist.

4. “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35” by Bob Dylan

4. “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35” by Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan is fine, but I hate this song. The green-eggs-and-ham lyrics, the falsely merry laughs and shouts in the background, the tediously dogged percussion, the unvarying oompahs—it feels like a joyless march straight to hell. When asked about this song, Dylan said “I never have and never will write a drug song.” (Don’t be disingenuous, come on, you totally did, it’s precisely this song, you’re just embarrassed to admit it!) But let’s take Dylan at his word: what’s this song about, then? Dylan says: “Cripples and Orientals and the world in which they live… It’s a sort of Mexican thing, very protest… and one of the pro-testiest of all things I’ve protested against in my protest years.” Um, sure thing, dude!

For me, this song has the insinuating, “who-me?” grin of someone who means you ill. The narrator of Dare to Know is frightened of this song as a child—looking back as an adult, he’s bothered at how Dylan “is so maniacally insistent about it, why is he so invested in everybody getting stoned? Especially when he goes on to say, ‘They’ll stone you when you’ do this or that—what does that even mean? If you don’t get yourself stoned on Bob Dylan’s fucking schedule, he’ll send somebody to do it to you?”

I didn’t want to include this song on the list, but in the end I had to, as an example how cursed pop music can feel. In a way, this song is as relentless as the previous Slikback track—but where Slikback feels like the clicks and whirs of a perfectly clean machine, here that machine has grown masses of dirty hair and is buried under a creepy shaggy 1960s vibe. The mocking haw-haw-haw-haw of the trombone and harmonica, the overall sliding-into-a-degenerate-state feeling—it makes me feel like all of life is a grisly cartoon.

5. “Andrew Void” by Mica Levi

5. “Andrew Void” by Mica Levi

This is from the soundtrack to the underrated 2013 movie Under the Skin. I love this movie and I adore Mica Levi’s soundtrack, which I listened to on repeat while writing Dare to Know. Like the Slikback track, this song feels like a glimpse into the secret structures vibrating beneath the other songs on this playlist.

In Under the Skin, a three-note “seduction” motif repeats in the soundtrack in the scenes when the movie’s extraterrestrial vamp lures another hapless victim to its doom—a spooky riff that feels to me like it expresses an inhuman, curious yearning. This song’s queasy amalgam of intimacy and detachment also captures the atmosphere of Dare to Know’s thanaton calculation process, which is similarly both dispassionate and ecstatic. “It gets omitted from the histories so people think our algorithm runs on pure logic,” says the narrator. “But no, something hungry and invisible around us demanded to be acknowledged and sated.” The call-and-response of the metronomic drums feels like a programmed scanning subroutine; the violin set against it feels like some alien entity that is active, inquisitive, seeking, merciless.

6. “Into the Groove” by Madonna

6. “Into the Groove” by Madonna

After “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number),” this is the most important song in the book—it’s the song that is playing when the narrator and his girlfriend Julia have their first kiss, and it’s the song that is playing in the final scene of the book, when we enter a kind of metaphysical locked groove, a single moment from our narrator’s life repeating forever.

For me, it’s a great dance song because it’s both a lonely song (“I’m tired of dancing here all by myself”) and a kind of taunting, challenging song (“Boy, you’ve got to prove your love to me”). Some lovelorn songs feel dedicated to one person: I love you and only you! Other songs feel like a general invitation: Anyone will do, let’s just get off! This song feels special to me because it sounds like a heartfelt come-on, and yet a strangely impersonal one—here Madonna could be the chipper analogue to the lethal alien in Under the Skin. But it’s that very impersonality that expresses, more effectively than a conventionally romantic song, the ungovernable, tasteless, indiscriminate overflow of desire you have when you’re young. And when that desire for just anyone suddenly—maybe without you realizing it at first—focuses on one and only one person, it’s like an ocean getting channeled through a canal, it’s a shock. You didn’t know you had it in you, to feel that intensely for one person. And at the end of the book, when we literally and eternally get into the groove, we understand what Julia meant to him. Now I know you’re mine.

In Dare to Know the narrator says, “For me the eighties meant a time of clean lines. Top 40 music sounded cleanly synthetic . . . Things that were meandering, bearded, shaggy, bloated, natural, organic: out. Things that were straightforward, lean, engineered: in.” This song fulfills that 1980s promise: it has a slick sheen, a reptilian, mechanical, yet alluring surface. It may be music for cheesy robots, but there is relief in letting yourself be a cheesy robot; for our narrator, it’s certainly preferable to what he feels are the creaky olde-tymey wheezings of the 60s and 70s.

7. “I Know No One” by Mount Eerie

7. “I Know No One” by Mount Eerie

This is a good chaser for “Into the Groove” because it’s so spare and melancholy and handmade-feeling. There’s always a part of you that is inexpressible, even to those you love most and feel closest to. Even as the narrator’s relationship with Julia progresses, they still don’t totally comprehend each other. “Do you fall in love with someone because you understand them?” muses the narrator. “Not a nineteen. It’s their otherness that draws you in.” It’s a lonely song, and the heartbeat percussion, the swelling background drone, the pacing-in-frustration guitar all build up to the song’s abrupt end: “But tonight we will find out / I know no one, and no one knows me.” But by the end of Dare to Know, when our narrator comes face-to-face with how seriously he has blown their relationship, he begins to grasp his own myopia: “Julia did know me. I had never really known Julia. I had never seriously tried.”

8. “Temptation Eyes” by The Grass Roots

8. “Temptation Eyes” by The Grass Roots

The narrator of Dare to Know cherishes his memories of hanging out in the basement of his former girlfriend Julia’s childhood home, which has a jukebox stocked with 45s from a particular era of pop music (late 1960s to the early 1970s—mostly Motown and rock and roll). These songs sidestep the bogus distinction the narrator and his friend Renard had made between “shaggy, druggy” 1960s music and “clean, mechanical” 1980s music. And yet even these songs have a disquieting edge to them. “Temptation eyes, looking through my soul”—when we finally meet Xuuzi, the weird figure that has a crucial relationship to the narrator, those lyrics will gain a new, unexpected meaning. Here we see that even in the narrator’s casual, everyday memories, the “vast invisible thing” is always present, demonically speaking to him and us through Top 40 music.

9. “Smiling Faces Sometimes” by The Undisputed Truth

9. “Smiling Faces Sometimes” by The Undisputed Truth

Another seemingly-anodyne, oddly-foreboding pop song from Julia’s family’s jukebox. Later, through the entity who calls herself Xuuzi, the narrator will meet another person who seems to have Julia’s face—but what is that entity really, and what is its relationship to the narrator? “Smiling faces show no traces / Of the evil that lurks within (can you dig it?)” This is the mystery that drives the latter third of the book, when we come into closer contact with the enigma of the Flickering Man, a weird computer graphic that our narrator first encounters in a haunted video game in high school. “He almost had a smile on his face, although that couldn’t be because his graphic was identical to my man, and my man’s face was expressionless. But the Flickering Man was somehow smiling.” Can you dig it?

10. “San Cristobal De Las Casas” by Swirlies

10. “San Cristobal De Las Casas” by Swirlies

This is kind of noisy-but-fey music our narrator listens to as an undergraduate in college: aggressively curated indie obscurities, arty and unsexual, too fussy to fuck to but still possessing some driving momentum. Although this song lacks any punk edge, it has a noisy spark that makes it occasionally, improbably, rock. It also has an odd, insistent “locked groove”-feeling section in the middle that mirrors Julia’s idea of what happens after one dies, and what happens at the end of the book—repeating a certain crucial moment forever. “At one point the record began to skip… the skipping had its own rhythm and made its own pulsing song. We were conspiring with it by dancing inside it.”

11. “Summertime Girls” by Y&T

11. “Summertime Girls” by Y&T

This is a deliberate contrast, almost a rebuttal, to the previous song. It’s the kind of song that’s being played at the party of townies that Julia takes our narrator to after their dubious first date, where our narrator hears music he describes as “unironic classic rock and bad metal”—or more precisely, in this case, the kind of music that the Beyond Yacht Rock podcast pegged as “Camaro Summer.” That is, upbeat 80’s beefy blue-collar pop-rock that celebrates good vibes, “the kind of songs that would sound perfect coming from a Camaro cruising a beachfront street in the mid-1980s.” This song is opposite to the kind of music our narrator prefers (and so much the worse for our narrator); by the early 90s, when this scene occurs, such stupidly great anthems are out-of-date in a way our narrator finds difficult to bear. Whatever! A song like this might be dumb, but golden retrievers are dumb too, and they’re awesome! There are certain forms of awesome you can only access through the dumb. (The name of the band, Y&T, stands for “Yesterday & Today”—which, serendipitously, echoes the name of the Beatles LP that features the unsettling baby-massacre image on the cover that long haunted our narrator. Even when the most goofball, mindless-fun 80s rock is playing, the “vast invisible thing” quietly whispers its presence.)

12. “Intro Cymbal Wind” by Dean Hurley

12. “Intro Cymbal Wind” by Dean Hurley

Dean Hurley is a sound engineer who often collaborates with David Lynch. This haunting track is taken from an album of incidental noise and music from Twin Peaks, which why I include it here, for the influence of David Lynch is very much part of the DNA of Dare To Know. This atmospheric interlude expresses the spooky energies seething beneath all the songs on this playlist, and also acts as a bit of a necessary sorbet between the more conventional pop songs. I love that creepy buildup to the ominous WHOOSH at the end!

13. “Band of Gold” by Freda Payne

13. “Band of Gold” by Freda Payne

Here’s another song that was mentioned being on the jukebox in the basement of Julia’s childhood home. It’s another catchy, seemingly upbeat song that is actually about loneliness and suspicion, about failing to come together, about missing your chance. The jukebox, it turns out, was warning our narrator all along. When he has his fateful encounter with Xuuzi in the hotel room, the lyric “I wait in the darkness of my lonely room / Filled with sadness, filled with gloom / Hoping soon that you’ll walk back through that door / And love me like you tried before” comes true in a nightmarish way that sets his whole life awry. “That day I changed. I never felt lonely before. Now, lonely all the time.”

14. “Neetriht” by Hali Palombo

14. “Neetriht” by Hali Palombo

I am fascinated by the work of Chicago artist and musician Hali Palombo, who specializes in creating haunting sound landscapes out of found audio, often featuring shortwave radio. This mournful track puts me in the mind of the uncanny thanatons buzzing invisibly throughout the universe, and the occult process of calculation that makes them give up their secrets; this piece’s repeated ghostly warbling repetition of four descending notes fits in with the book recurring four-stage declining scheme of Gods-Heroes-Commoners-Chaos that is tied to the four-stage life cycle of thanatons themselves, and was first introduced into the story by the Beatles’ “You Know My Name (Look Up The Number).” Philip Montoro interviews Hali here for the Chicago Reader, and she’s a fascinating person. This is the first of four Hali Palombo tracks in this playlist; for me, her lonely, enigmatic, evocative sonic sensibility fits Dare To Know perfectly.

15. “Muskrat Love” by Captain & Tennille

15. “Muskrat Love” by Captain & Tennille

I remember, as a small child, sitting in the dentist’s office as a hygienist was going to town on my teeth, and hearing this song. Maybe I had heard the song before then, but as the hygienist jabbed and scraped at my teeth, I focused on it to distract myself—and I remember thinking to myself, even at a young age: What the hell is this?! Julia in Dare To Know hates this song, which is also on her jukebox. Even though I wouldn’t listen to this song for pleasure, it gives me great satisfaction that something this weird and off-putting was once on the actual radio, that real people purchased and enjoyed it. What a strange and wondrous world we live in! The revolting combination of the cutesy and the sexual (“Sam says to Susie, would you please be my missy? Susie says yes, with a kissy!”) is soul-draining. The locked groove at the end, with its electronic squirts and farts repeating forever, might lead you straight into Lovecraftian madness. One of the most revolting, nightmarish songs of all time, listening to it will always feel like having my teeth cleaned, forever.

16. “Glenn” by Slint

16. “Glenn” by Slint

I love everything by Slint. Their hypnotic music is made all the more impressive because they were barely out of their teens when their final album Spiderland was recorded. I like this particular song because it feels like someone pacing through an endless maze: constantly on the move, seemingly getting somewhere, but in fact going nowhere, and nothing changes. It puts me in the mind of the scenes in Dare to Know when the narrator is obsessively playing Renard’s strange video game, getting deeper and deeper into it, like a dream you can’t wake up from: “The game really was addictive in an obsessive-compulsive way, and I found myself spending hours in my basement on my computer, drawing maps and exploring every last corner of the vast, mysterious house. But now that I was playing it intensely, and not just casually, I realized how the game really made no sense. I couldn’t even figure out what I was supposed to do. It always seemed like I was making progress, little by little, ascending level upon level in the house, but I didn’t know where it was going, what it meant.” For me this song expresses that feeling you have when you’re in your late teens and early twenties, that expectation that true meaning and satisfying release are always just around the corner, but somehow they never show up, and yet you keep on going, with the growing half-suspicion of antagonistic forces previously unreckoned-with underneath it all.

17. “The Limit” by Class Actress

17. “The Limit” by Class Actress

I feel this is the kind of song Xuuzi would be dancing to at the club, when she seems to be taunting the middle-aged narrator whom she has dragged along for their weird date. This is one of the lesser Moroder-produced dance songs from the 2010s, but it feels like a 1980s song, almost Donna Summer-y. I love this song, but even still, it certainly represents for me a kind of decline and exhaustion, a repetition of forms from previous ages, a vain hope perhaps for some of the old magic to reoccur. But such magic can’t reoccur—not for us, and not for our poor narrator. Xuuzi isn’t Julia. Even still, in the end, the narrator and Xuuzi will fatefully go to “the limit” that the song promises: “Want to see how far I’ll go, baby do you really want to know?”

18. “Let’s Go Crazy” by Prince

18. “Let’s Go Crazy” by Prince

After their awkward date, “Xuuzi” and the narrator return to his hotel room and wind up dancing to the entire album of Purple Rain, streamed out of Xuuzi’s phone. This choice on Xuuzi’s part baffles our narrator at first: “Maybe playing it was her considerate choice for an aging gentleman like me—an oldie? Some classic rock?” But their ecstatic dancing and ingestion of the “weird shit” drug Xuuzi had procured is a prologue to their mutual vision of their “hideous kingdom”—as Prince says, “there’s something else: the afterworld.” Prince is from Minneapolis, a twin city to St. Paul, just as our narrator and the-thing-that-calls-itself-Xuuzi are twins: eschaton to anti-eschaton. Prince says “Instead of asking him how much of your time is left / Ask him how much of your mind, babe”—advice that our narrator, whose job is to tell clients “how much of your time is left,” would’ve been well-advised to heed. And yet, perhaps dancing with someone like Xuuzi is exactly what our narrator needs. “Soon all that is flushed out of my head and I am dancing, Xuuzi and I are dancing, dislodging ourselves from the vast invisible thing, getting free.” Just as Prince says later in the song, and as Xuuzi will tell him later that night: “We’re all gonna die.”

19. “Scene D’Amour” by Bernard Hermann

19. “Scene D’Amour” by Bernard Hermann

I first saw Hitchcock’s astounding Vertigo when I was in middle school. It’s a foundational movie for me. I’ve watched it again and again over the years, and I get something different out of it every time. It was inevitable that some aspects of my book would take their cue from Vertigo (yet another reason Dare To Know’s Saul Bass-esque cover design is so perfect!). In particular, our narrator’s attraction to Xuuzi as an inferior copy of his lost love Julia is inspired by Vertigo’s portrayal of Scottie’s attraction to the crass Judy as a kind of substitute for his former love, the more elegant Madeleine—with Scottie going so far even as to force Judy to dress and act like Madeleine. This track is the song that plays after Scottie gets Judy to agree to wear her hair like Madeleine’s and change into a dress identical to Madeleine’s—the song that plays when Judy comes back into the room, seemingly fully transformed into Madeleine. The music swells romantically, encouraging us to feel that this is an emotional high point, but it’s really only about the one-sided gratification of Scottie’s obsession; perhaps that is why Hitchcock drenches her appearance in sour, green, alien glow. Similarly, when Xuuzi emerges from the bathroom completely transformed into Julia (or as she says: “I am wearing Julia”), the narrator is seemingly getting exactly what he wants, but that is only unlocking the door to the more harrowing next part of his journey.

20. “Galva” by Hali Palombo

20. “Galva” by Hali Palombo

Another weird sonic interlude by the brilliant Hali Palombo. The events arising from the narrator’s rendezvous with Xuuzi have plunged the universe in a metaphysically destabilized state, and now the background calculations that lurk behind all of reality have become active and expectant. This track’s jittery drone, algorithmic-sounding sonic loops, and mechanical jabber all combine to make it sound as though the thanatons are frantically processing again and again the event of the narrator’s eschaton and Xuuzi’s anti-eschaton beginning to converge, and not coming up with acceptable answer. The thanatons are starting to break down, and this track gets across the feeling of the calculations quivering and splintering in the background of the narrator’s life after his and Xuuzi’s close encounter. “That’s when I felt that, from here on out, I was just marking time. Then time did run out. 7:06 p.m. yesterday. And yet I’m still here.”

21. “From Mesa and Plain, Op. 20: No. 2. Pawnee Horses (version for chorus)” by Arthur Farwell, University of Texas Chamber Singers, James Morrow

21. “From Mesa and Plain, Op. 20: No. 2. Pawnee Horses (version for chorus)” by Arthur Farwell, University of Texas Chamber Singers, James Morrow

After Xuuzi ushers our narrator into a psychedelic vision of “their hideous kingdom,” he enters a deeper waking dream that seems to be occurring inside the hotel, in which he seems to be the chief honoree at some ceremony attended by all the employees of Dare To Know. Baffled and exhilarated, he takes part in the ceremony, which at first it seems like an jubilant occasion, and this song’s triumphant, angelic sound captures that quite well. He feels himself exalted among his Dare To Know colleagues—but just as there is a kind of ominous, expectant feeling to the ceremony, there is an ominous, expectant element to this song, with the uncanny rise and fall of its chorus. When the dream begins to fracture, and he glimpses for the first time Dare To Know’s connection to the practices of ancient Cahokia, the urgent chorus of this song unexpectedly but appropriately twists up into a final, surprised shriek: “Then Renard spoke, and we were all Flickering Men.”

In our time, how do you reckon with a composer like Arthur Farwell, an exponent of the mostly forgotten “Indianist” school in American classical music? As he took his inspiration from studying Native American songs, nowadays one might dismiss Farwell’s work as appropriation, or even kitsch. To be sure, in the context of his time Farwell had a genuine reverence for Native American music, and advocated respect for his inspirations. Still, such music may sit uneasy with us today. Since part of Dare to Know is about events that occurred in the lost Native American city of Cahokia a thousand years ago, and their influence on modern America, perhaps the best way to express that equivocal, unresolved relationship is with this ghostly, frenetic, “problematic” song.

22. “Oblong” by Hali Palombo

22. “Oblong” by Hali Palombo

After his fateful encounter with Xuuzi, “life took its long lonely left turn.” The narrator searches for Xuuzi but can’t find her—indeed, can’t find any evidence she ever even existed. His marriage collapses, he grows distant from his sons, business starts to go south, he starts drinking heavily, he can’t sleep. This track, another banger from noise witch Hali Palombo, feels like what is secretly going on in the metaphysical background while the narrator’s life is falling apart: the ceaseless mechanical babble of the thanatons as they self-calculate, busily processing the singularity of his meeting with Xuuzi, and the freaky consequences of it. Was the whole hallucinogenic episode was just a kind of near-miss? Or some sort of rehearsal? Or a prophecy of what’s to come?

23. “Sure As Spring” by La Luz

23. “Sure As Spring” by La Luz

Our narrator calculates his death date, and discovers that he had “died” twenty-three minutes ago. He’s clearly not dead, but the math is never wrong, so what gives? He and his ex-girlfriend Julia had performed a similar calculation back in college, but never took the crucial last step. Our narrator hopes Julia still has the calculations, so he can check his anomalous result against it. On impulse he flies from his home in Chicago to San Francisco, where Julia lives now. But is it just the confirmation of the calculation he wants? Or is there unfinished emotional business between them? Why is he really flying to California?

I love the music of La Luz, which on the surface sounds like classic surfer rock with girly doo-wop harmonies. But this airy insouciance has an eerie, uneasy undercurrent; such a combination is very California. “Sure As Spring” expresses the unstable mood our narrator has once he comes out of the airport in San Francisco, ready to meet Julia that night: jaunty and venturesome, but also desperate and sad. “When you were mine,” sighs this song wistfully, sliding straight into a matter-of-fact declaration: “Now I kinda wanna die / And that’s the truest way to know that I’m alive.”

24. “Dream Come True” by The Temptations

24. “Dream Come True” by The Temptations

This song comes at the emotional and exegetic pivot of the book. Our narrator is attending his ex-flame Julia’s wedding to Keith, a man whom he ungenerously pegs as a good-natured fool. Earlier in the wedding, our narrator and his girlfriend Erin endure a conversation with another guest who describes to them an idiosyncratic take on Plato’s cave that focuses not on the prisoners in the cave, nor the puppeteers entrancing them with a shadow puppet show, bur rather on the shadows themselves—in this telling, the shadows are the heroes, straining to become the realities of the things they represent. Later our narrator has some awkward social interactions with Julia, but it’s not until the end of the night, when this song is playing, that he comes to his most painful realization.

“Dream Come True” is one of the songs that would play on Julia’s basement jukebox. Our narrator hasn’t heard it for years. And as he says, “Nothing about this song should work. The lyrics are nothing special. The lead singer seems to be singing a completely different song, only coincidentally syncing up with the rest of the band. It’s an accidental-feeling overlapping of clunky parts that shouldn’t fit together, but the thing is, the song does come together, by the skin of its teeth, its near failure making it exhilarating, the song would fall apart if just one of its many impossible-to-justify choices was different.” And this sparse, haunting song encapsulates many things about the story at once.

As our narrator listens to the song, he watches a little boy and girl slow-dancing; then he notices that Julia is there too, also watching the children, with “a raw look in her eyes. I had never seen Julia look so empty.” When Julia glances up and notices he is watching the kids too, her expression changes for a moment, but that moment tells him everything he needs to know about himself, and how badly he had treated her. “When did I become such an asshole?”

This song also suggests the metaphysical relationship between the eschaton and anti-eschaton, two yearning entities searching for each other for centuries to fulfill a long-overdue apocalypse: ”I don’t care where you came from / Oh no, I don’t care what you’ve been / All I know, is that I love you / And I’m going to love you till the end.” The song is also about the shadows in Plato’s cave; “dreams” that desperately want to “come true.” It’s not for nothing that, during his date with Xuuzi, when our narrator asks her for the name of the “weird shit” drug they’d be getting high on in the hotel room, she only replies “Dream come true.”

25. “Wild Jungle” by Machito

25. “Wild Jungle” by Machito

Our narrator visits his married-and-moved-on ex Julia in San Francisco, and she amiably invites him to dinner at home with her husband Keith and their three children. Our narrator had underestimated Keith, “who’d gone from shitty midwestern improviser to jackpot-level screenwriter, and then, even more improbably, to film producer” at what seems like a Pixar-like company. Acutely aware of his own broken marriage, alienated sons, and barely-scraping-by career, our narrator feels awkward and bungling in their beautiful house with this happy family. He starts drinking to loosen up, and indeed might be getting indecorously drunk, perhaps even blurting inappropriate and humiliating things in front of the children—or wait, does he? It’s not always clear how bad it gets, and when I wrote this scene I wanted to get across the flushed, impulsive, buzzed sense when you’re in a social situation and not sure if you’ve had too much, and the “fuck-it” attitude that comes on when you decide to go for broke anyway. At one point one of the daughters starts explaining the plot to Keith’s new computer-animated movie, and she puts on the soundtrack of that movie, which features “jaunty, 1960s-style mambo music.” I chose this particular mambo track because it expresses well our narrator’s inebriated mental state—it feels like it’s teetering on the edge of out-of-control, a little too helter-skelter, a little too fast, a little too desperate and reckless.

26. “Hotel” by Hali Palombo

26. “Hotel” by Hali Palombo

Thanatons are subatomic particles that can be used to predict human death; eschatons are subatomic particles that can predict the death of the entire universe. After a disastrous reckoning with Julia, our narrator drunk-drives back to his hotel, but on the way the final puzzle-pieces he needs to solve the mystery of the eschaton begin to fall into place. Back in the hotel, he works late into the night on his calculations, trying to identify the nature of the eschaton, determining (or perhaps generating) the death-date for the entire universe. This eerie track gets across the groggy, half-drunk, half-caffeinated, dreamlike mental state of the narrator as he chases the truth of the eschaton through a an ever-deepening and complicating phantasmagoria of math, myth, and personal revelation. This is the last of the four songs on this playlist by audio Bene Gesserit Hali Palombo, whose sonic landscapes feel tailor-made to the experience I want this book to express.

27. “Kuulen ääniä maan alta” by Oranssi Pazuzu

27. “Kuulen ääniä maan alta” by Oranssi Pazuzu

Here’s another song recommended by my good friend Philip Montoro, who has forgotten more great music than I will ever know. I asked for “a fantastical soundscape of the ‘next world’ where everyone is weird metal dragons in a blinding desert,” and Philip suggested his “favorite Finnish psychedelic black-metal weirdos.”

Well, what can I say? Philip hit the bullseye again! The end of Dare to Know is a time-shifting, reality-breaking ritual taking place at the offices of the Dare to Know company in San Francisco, which echoes and connects with similar rituals of mass human sacrifice throughout human history, including in Cahokia a thousand years ago. In many stories, the end of the universe is something that must be prevented or thwarted, but in Dare to Know our universe has persisted for far too long, and should rightfully end; the antagonists are those who are forcing the universe to persist, thwarting its end through a periodic mass human sacrifice that prevents the strange and beautiful new thing that could be born out of the universe’s ending. This unsettling, relentless song feels as though the “vast invisible thing” hinted at throughout this playlist finally gets to speak unfiltered—to be sure, I don’t know what the lyrics of this song actually mean, being in Finnish, but they feel grisly. The mechanical reproduction of the Cahokia carnage, and the periodic human sacrifice of ages past, is well expressed by this malevolent-feeling song. And yet, for me, the progress of this song also aligns with how our narrator breaks through this death-ritual, and finds his own way to cleanse the eschatons and thanatons, saving all the souls in our universe—not leaving them to die in the old world, but leading them to a new existence in the next world where the shadows become realities, and dreams come true.

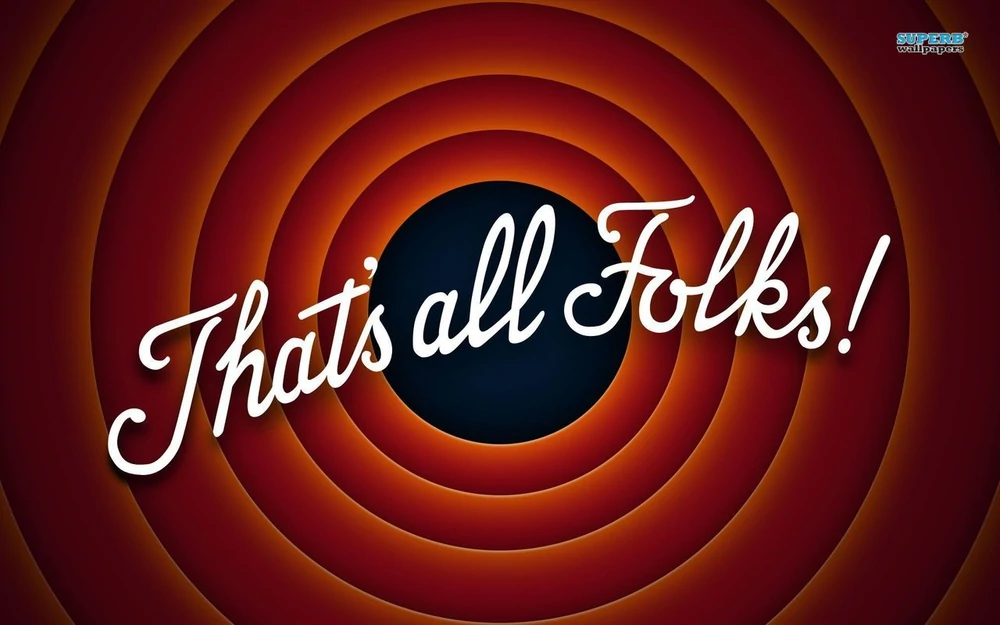

28. “Looney Tunes Theme”

28. “Looney Tunes Theme”

I live in Chicago. Many Chicagoans, sooner or later, take an improv class. I enjoyed taking improv classes because it was good for my writing, but I had no desire to do improv onstage for a paying audience. So I would complete the sequence of classes, but then quit right before the big show, let a year or two pass, and then start up the classes again.

Along the way I learned about the lore of Chicago improv comedy—in particular about its great-grand-daddy, Del Close. He died before I ever set foot in Chicago, but I loved reading and hearing stories about him, because he seemed to be one of those larger-than-life maniacs—a drug-fueled visionary, an abusive blowhard, a comedic genius, an exasperating grifter, a practicing warlock—a Charles-Manson-but-without-the-murder kind of fella. We share a birthday, March 9th.

Anyway, I was reading a biography of Del Close, and it described how he and his friend would get high and speculate what dying would be like, which Del’s friend expected to be “brightly colored concentric circles close about your field of vision, and you see—written in front of you in backwards script, ‘That’s All Folks!’”

That passage stuck in my head for years. So I took that single sentence and adapted it, expanded it, and made it a bit more elaborate for the scene in Dare To Know in which the narrator’s summer camp roommate Renard describes what he thinks happens when you die—and what happens in this scene.

But that’s just one theory in Dare To Know of what happens when you die, the nightmare version. Later on in the book, Julia puts forth her own idea of what happens when you die: that you live and relive a significant moment in your life, like a record player needle caught in the locked groove at the center of an LP, and you continue reliving that moment until the needle kind of wears down, and you and the moment dissolve.

Maybe the stakes of Dare to Know could be summed up this way: which death-vision is correct? Renard’s? Julia’s? Or something else?