Interview with The Weirdside

|

|

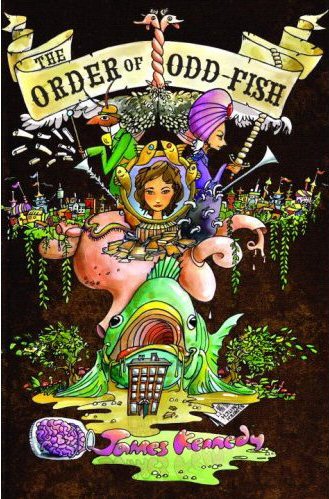

A couple weeks ago I posted an in-depth interview with a blogger who disliked my novel The Order of Odd-Fish.

Here’s the opposite: an interview with a blogger who LOVED Odd-Fish!

It’s Adam Callaway, absurdist-lit writer and master of the blog The Weirdside. The interview is cross-posted there. (He’s the one with the clock on his head. I’m the one with the merciless baby editor.)

We talk about comedy theory, what makes a good title, the upcoming Odd-Fish fan art gallery show, and Dig Dug. And more. Let’s get cracking!

ADAM: The Order of Odd-Fish is many things, but one of the main things is humor. How do you write humor? Do you carefully plan out each joke or do they come more by happy accidents?

JAMES: For me, the best humor comes from character. If the characters are fresh and distinct, and their relationships with each other have a natural push-and-pull, then the jokes will flow almost without effort.

Screenwriter Jane Espenson (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, Battlestar Galactica) had a blog in which she explained various tricks of screenwriting, with particular emphasis on comedy. I came across it while I was in revisions, and I found it very helpful. Jane makes a distinction between “soft” jokes and “hard” jokes that’s worth exploring.

Screenwriter Jane Espenson (Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Firefly, Battlestar Galactica) had a blog in which she explained various tricks of screenwriting, with particular emphasis on comedy. I came across it while I was in revisions, and I found it very helpful. Jane makes a distinction between “soft” jokes and “hard” jokes that’s worth exploring.

A “hard” joke is like an equation, with every word precisely in place, a glittering nugget of funny. If well-written and delivered well, then joke for joke, hard jokes get the biggest laughs. The sharp, lethal put-down is often a hard joke. Here’s a chestnut from Dorothy Parker: “If all the girls who attended the Yale prom were laid end to end, I wouldn’t be a bit surprised.”

(Notice that the word that makes the whole line funny is the last word? I’ve found that if I’m working on a line that has humorous potential, but it just isn’t funny for some reason, often the way to fix it is to rearrange the words such that the last word is the one that unexpectedly changes and makes funny everything that came before.)

The danger of a hard joke is that it can feel canned, written, sitcommy—something too clever that no actual person would ever really say. A hard joke is often something that anyone could say and it still would be funny—but wait, that’s good, right?

Actually, no. In a novel, jokes can’t just be funny; they must also develop character. Otherwise you have a bunch of joke machines nattering at each other for 200 pages or more, and that’s just wearying.

“Soft” jokes, on the other hand, are often not as immediately laugh-out-loud funny. They spring from the peculiarities of character, and are usually very context-specific. But the accumulation of many soft jokes, and the way they reveal character, makes them more powerful and ultimately funnier than a similar amount of “hard” jokes.

Here’s an example from Napoleon Dynamite:

Deb is selling crappy handicrafts door to door. Napoleon answers the door; his boorish brother Kip is inside watching some haw-haw sitcom.

DEB. In here we have some boondoggle keychains. A must-have for this season’s fashion.

NAPOLEON. I already made like infinity of those at scout camp.

DEB. Well, is anyone else here? I’m trying to earn money for college.

KIP (off-camera): Your mom goes to college.

It would be a sin kill the effortless genius of this scene by overexplaining it, but in the interests of analysis, let’s sin.

None of these lines is funny on its own like the Dorothy Parker line above, but taken together, and especially in the context of the rest of the movie, they’re funnier than the Dorothy Parker line. Why? Because with every line, each character unintentionally reveals their absurdity. We all unintentionally give ourselves away every time we open our mouths. The disconnect between what a character thinks they’re saying, and what they’re accidentally divulging about themselves, is fertile ground for comedy. (It has to be accidental, something we read into the line. Napoleon wouldn’t be funny if he believed he was being funny.)

Napoleon’s combative dorkiness is out in full force with his line, which is perfectly worded (“like infinity,” “scout camp”). Stilted, listless Deb starts out by robotically mumbling a sales pitch (“in here we have some,” “a must-have”—nobody talks like this outside a sales context) and then breaks down into a plea. But the masterstroke is Kip’s “Your mom goes to college.”

Outside of certain limited contexts, it’s impossible to do a funny “mom joke”—that territory was strip-mined years ago. But there is such a thing as a funny joke-about-a-mom-joke, or a joke about a listless old white dude who makes mom jokes. The best thing about this mom joke, “Your mom goes to college,” is that it doesn’t make sense even on its own terms as a joke. It’s funny because it’s poking fun at the reflexive, mechanical, self-satisfied humor of people like Kip.

Jane Espenson has three valuable posts on the topic of soft vs. hard jokes here, here, and here. Indeed, her whole blog is a generous cornucopia of wisdom. It’s a free master class in comedy writing by an experienced professional.

As a postscript, there is a particular kind of “hard” joke that I’m very fond of, although it never makes me laugh. I call this joke the “Zen koan” kind of joke, for it does not cause laughter so much as it brings the reasoning mind to a gentle halt. From The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy:

FORD. You’d better be prepared for the jump into hyperspace. It’s unpleasantly like being drunk.

ARTHUR. What’s so unpleasant about being drunk?

FORD. You ask a glass of water.

I’ve never laughed at that joke. The first time I read it, I probably didn’t understand it, or even notice it. But it is now one of my favorite jokes in the Hitch-hiker’s series. It doesn’t make me laugh, but it does make my brain go “click” in a satisfying way, which is rarer.

I think a good comedic novel should have both hard and soft jokes, and if possible, the occasional Zen koan.

In this discussion, it would be a shame not to mention New Yorker literary critic James Wood’s brilliant preface to his book The Irresponsible Self: On Laughter and the Novel. In it Wood draws a distinction between “corrective” laughter, which he characterizes as satirical and bullying, and he claims has roots in religious writing, and “forgiving” laughter, which is more gently mocking, modern and secular. My tastes run towards “forgiving” comedy rather than “corrective” comedy. In any case, useful insights aplenty. You can read an abridged version of the essay here, but it’s worth it to go out and buy the book to read it in its entirety.

In this discussion, it would be a shame not to mention New Yorker literary critic James Wood’s brilliant preface to his book The Irresponsible Self: On Laughter and the Novel. In it Wood draws a distinction between “corrective” laughter, which he characterizes as satirical and bullying, and he claims has roots in religious writing, and “forgiving” laughter, which is more gently mocking, modern and secular. My tastes run towards “forgiving” comedy rather than “corrective” comedy. In any case, useful insights aplenty. You can read an abridged version of the essay here, but it’s worth it to go out and buy the book to read it in its entirety.

You’ve said that when you were shopping around Odd-Fish, you received over 100 rejections from agents. How did you stay chipper through all the negativity?

I didn’t stay chipper. It was completely demoralizing.

Do you feel like you’ve gained the right to humiliate those agents that said “nay” to you of/and or using costumes and pie?

Well, The Order of Odd-Fish hasn’t exactly set the world on fire, has it? Only if I’d written a bestseller would I have the standing to humiliate anyone.

Actually, I’m grateful for the rejections. They forced me to review my manuscript, again and again and again, each time with a more critical eye. For the three years I was trying to sell Odd-Fish, I was continually revising and rewriting and tightening. If I’d sold my first draft, it wouldn’t have been as good a book.

Do you put value in the trope that you need to live life before writing believable characters and plot?

Wait. In what situation do you not need to “live life”?

What’s your take on titles? Are they important or secondary? Do you prefer complex or simple titles?

Titles are important. I have a pet idea about titles that I might as well share.

Ideally, I believe a good title should feel like the DNA of the book—that all the conflict, structure, atmosphere, and sensibility of the story should somehow be there right in the title, writ small in a couple words. The telling of the story is simply the unpacking, the unspooling of what’s already crammed into the title.

Titles that manage this trick have a magnetic tension in them, a fertile busyness. You can feel the different words of the title pulling each other in different directions. Those titles are unforgettable. They intrigue you afresh every time you hear them, even if you’ve already read the book.

|

|

For instance, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe is a fantastic title. We feel three distinct things pulling against each other—something noble, something evil, and something commonplace. Adding and the Wardrobe to the end is the masterstroke, because it deflates the epic-ness of the first two items, and brings the title back to earth. It assures us that even though there will be fierce animals and unnatural magic, there will also be a certain coziness. That coziness is essential; it throws the magical stuff into relief.

The Hitch-hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy is another great title. You can feel the unpretentiousness and raffishness of “hitch-hiker” rub up against the cosmic grandiosity of “galaxy.” Again, the last word turns everything around. “Galaxy” instantly recontextualizes all the preceding words, making the title buzz with tension. And the two words beginning with H, followed by the two words beginning with G, is a nice piece of alliteration, but not so much that it bonks you over the head.

A certain kind of good title posits something that at first sounds like an impossibility. Margaret Atwood’s The Blind Assassin (Huh? How could an assassin worth their salt be blind? I’d better read it and find out!). G.K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday (Wait, how can a man also be a day of the week? I’m intrigued, tell me more!). Neil Gaiman’s American Gods (But there are no home-grown American gods! Ah . . . )

|

|

|

|

Some titles try too hard. Throw in too many conflicting concepts, and you just get a mess. I love Angela Carter’s The Infernal Desire Machines of Dr. Hoffman, but the title itself is a mish-mash, almost impossible to remember. Even now I had to visit my bookshelf to make sure I was getting the title right.

So that’s what I tried to do with The Order of Odd-Fish. The words Order and Odd can’t bear to be in the same title together; they’re pushing and pulling, you can feel them fighting each other. Odd things don’t feel orderly; well-ordered things aren’t odd.

But throwing two opposing concepts together in a deadlock isn’t quite enough. We need the third thing (the third heat?), like Wardrobe, to liberate the energy pent-up between Order and Odd. And so Fish—something alive, something faintly disgusting, with religious overtones, but strangely alien to humans—comes along as the last word of the title, recontextualizes what came before, and releases the charged energy stored between Order and Odd. As a bonus, there are three words beginning with O in the title, giving us some pleasant alliteration.

At least, that’s my analysis after the fact. When the title first came to me, it was just out of the blue.

Odd-Fish is a cinderblock, but has a great flow. Do you see yourself as more a maximalist or a minimalist?

I just had to look up “maximalist.” After reading the Wikipedia page, I’m still at a loss as to what it means.

However, if I was asked whether I preferred a luxuriant, overflowing garden like Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, D.C., or a precise, formal Japanese garden like Ryoanji in Kyoto, I’d say I loved them both, but I’d probably spend more time at Dumbarton Oaks.

|

And if you give me the choice between fake Gothic architecture and authentic modernist architecture, I’ll take the fake Gothic.

|

|

(These buildings are across the street from each other the University of Chicago. It’s not quite fair—to my mind, the SSA building isn’t the best modernism can offer—but if I never saw another Mies van der Rohe glass box in my life, I wouldn’t miss it.)

The point is, I feel more at home with generous, baggy, forgiving art better than strict, clean, controlled art. I like when characters have a vitality that causes them to overflow their role in the plot, that allows them to be irresponsible in their duties to the story. I like it when stories can breathe, when they allow themselves to digress and evolve and surprise me, when the story momentarily forgets it’s merely a story, and for a little while feels like an authentic document from another world.

This liberating feeling of overflow can happen in both “minimalist” or “maximalist” writing. But I suppose the sentiment, on its face, sounds “maximalist.”

As evidenced by your amazing use of language and a little snooping, you are obviously well-versed in the classics. Do you read more for entertainment or a deeper meaning? What is your main priority when writing a story?

The only reason to read, or write, is for delight. To put yourself in the hands of an enchanter and allow them to astonish you—to be brash and obnoxious enough to try to be one of those enchanters—that’s the irreplaceable, exhilarating, non-negotiable thrill of stories. Everything else is secondary. Deeper meaning is something we construct for ourselves later, in our own idiosyncratic way, when we’re musing about what we read.

I’ve often found that if I think of a book, “Wow, this is deep, this is really good” as I’m reading it, then that depth is almost certainly fraudulent. Lasting depth is constructed in your head, after you’re done reading, and nourished by re-reading. Many of the books that are deepest and most meaningful to me seemed, on first reading, off-puttingly dry, arbitrarily silly, perversely turgid, superficially entertaining, etc. But that’s to be expected. Anything that’s truly original achieves that originality by doing something that, in the current scheme, is wrong. Not just “breaking the rules” but I mean wrong—it just doesn’t sit well with you the first time you read it.

But then it nags you. And you eventually come around. And then it seems like a brilliant innovation, and later, as an inevitable development. But when you first encounter something truly new, it seems incorrect, arbitrary, in bad taste. My goal is to think up stuff that shouldn’t work and make it work. If you think up ideas that sound like they would work right off the bat, then the excitement of creation just isn’t as electrifying.

You have a blog and a Twitter account and update them regularly. What do you think is the role of social media in the modern author’s professional life?

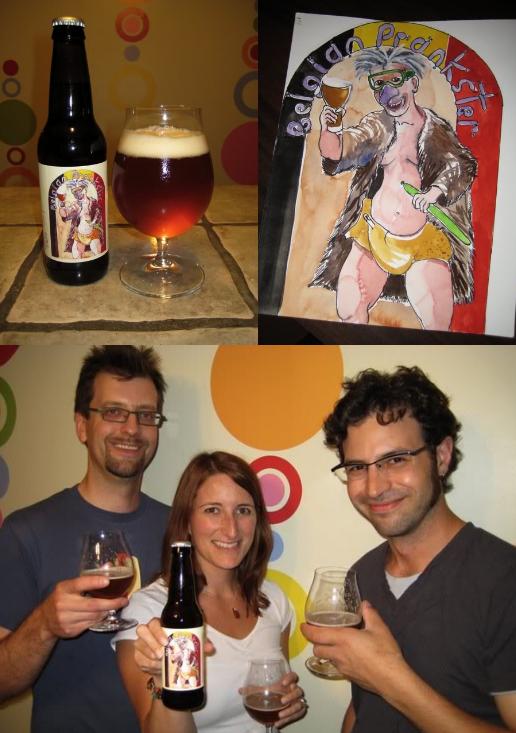

I usually blog once a week, maybe once every two weeks—that is, not very often. My twittering is pathetic. It does take time away from what I should be doing, which is writing stories. But the upside is that it’s given me a way to be in touch with my readers, and a showcase for the amazing fan art I’ve received that I’d like to share with the world—such as when a husband-and-wife team of brewers, Meg Rutledge and Matt Mayes, created a beer in honor of Odd-Fish’s villain, the Belgian Prankster. (The label is by Gabe Patti.)

|

Or when a Floridian named Elise Carlson surprised me by baking a cake that depicts the scene when the giant fish vomited the Odd-Fish lodge into Eldritch City.

|

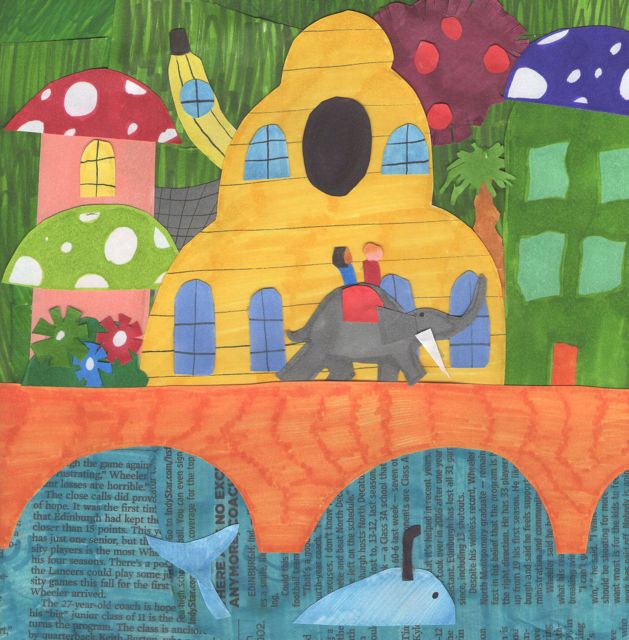

Or when Max Pitchkites, a high-school student, did mixed-media illustrations for all 28 chapters of the book. Some examples:

|

|

And other various other cool pictures, poetry, and costumes. Being in touch in this way gives me the chance to co-create the Odd-Fish universe with my readers. That’s a privilege, and an honor, and it’s worth giving up a little writing time for it.

Actually, I’m going to have a gallery show of this Odd-Fish fan art in Chicago in April 2010! More about that below.

Your blog reads more like a series of disjointed fevered dreams than personal entries. Why?

When I blog, I like to put a little effort into it. After all, I’m supposed to be a writer, so it’s a matter of professional pride to put out something nice. It didn’t seem worthwhile to write a blog that was simply ephemera; we’ve all read enough of those. You know the sort of blog: “I had a cheese sandwich today. Hey, how about that Tiger Woods? I’m almost done with the DVDs for this season of Dexter. Gosh, will it ever stop raining?” My day-to-day life is not interesting to those outside my friends and family, and so if I’m going to take the time to blog, I’m going to try to make each entry special. If it’s coming across as disjointed fever dreams, then MISSION ACCOMPLISHED.

Has your writing style/schedule changed since your daughter was born?

Yes. I don’t get to write anymore.

You live in Illinois (which I may point out, is below Wisconsin; interpret that as you like) Do you prefer deep-dish or New York style pizza? Toppings?

I interpret that to mean that Illinois is south of Wisconsin.

Deep dish pizza is simply gross. It’s an evil brick of cheese that sits in your stomach and tells you that it hates you. I hope I’ve eaten my last piece of “Chicago-style” pizza. Thin crust all the way. My best friend growing up, Dave Mancini, has a thin-crust pizzeria in Detroit called Supino that is the bee’s knees.

Why did you choose to become a writer versus a painter, musician, Irish Step-dancer, etc?

I have no talent in those areas. I occasionally get lured into a band, but that doesn’t make me a musician. I have always been the least valuable player in every band I’ve been in. That includes my last band, Brilliant Pebbles, now sadly defunct.

|

Now that Brilliant Pebbles looks like it might be over, what are you going to do to keep yourself busy in a non-writing related way?

To keep myself busy? I’m already too busy without trying to dream up new stuff to eat up my time! I’m actually relieved Brilliant Pebbles is finished; that means I will have more time to work on my next novel, which my editor expects to see in July 2010. I am horribly behind schedule. It’s called The Magnificent Moots, and here you can find some preliminary illustrations, as well as a link to me reading its introduction.

|

|

Between The Magnificent Moots, my family, and my job (I’m a computer programmer for the University of Chicago), there’s no time for anything else. It’s a pity, because such extracurricular activities inspire a lot of my writing. I wrote the majority of Odd-Fish while taking improv comedy classes at The Second City and ImprovOlympic. In terms of creativity and inspiration, improv and writing fed into and nourished each other.

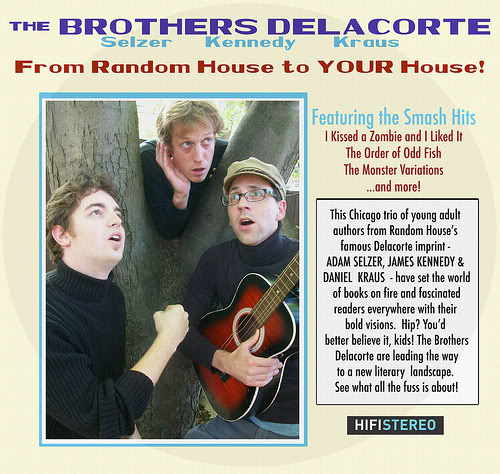

How and why did the Brothers Delacorte come together? What do you make of the allegations that its sole purpose is to show off how dashing you all look in turtlenecks?

|

Those allegations are sadly true. The Brothers Delacorte have done barely anything other than pose for those photographs. We’ve had two public readings, but getting us all in the same room at the same time is like herding radio waves. I’ve given up!

As for how we came together—fellow Delacorte author Daniel Kraus got in touch with me because he knew I was another YA author in Chicago who was on Random House’s Delacorte imprint. As it turned out, he worked right around the corner from me—as a reviewer at Booklist—and I worked at the American Medical Association at the time, a ten minute walk away. We started having occasional lunches, and are now cordial frenemies.

|

Weirdest scene from any book you’ve ever read?

The Circe chapter of James Joyce’s Ulysses. Never seen it topped. Don’t expect to.

What can we expect from Mr. Kennedy in the future, and when can we expect it?

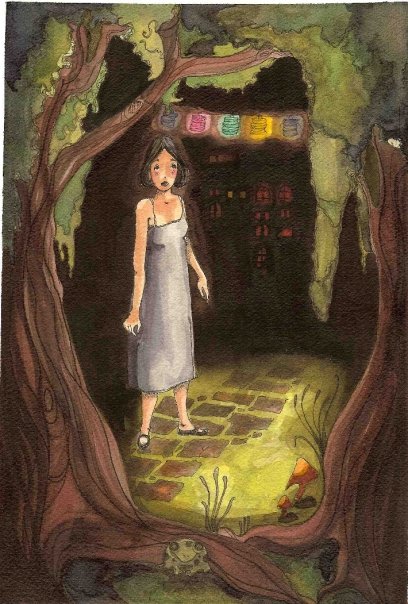

Glad you asked. As I mentioned in my remarks above, I’ve been getting a lot of wild, strange fan art for The Order of Odd-Fish since it’s been published. I’ve been putting them up in a special gallery on my web site.

|

|

Fan artists like this deserve broader recognition! So in April 2010 I’m planning a gallery show / extravaganza of Order of Odd-Fish art in Chicago. I’ve put out an open call for submissions.

|

Above image by Panndy from DeviantArt.com.

It’ll be not only an art show, but also a costumed dance party and theatrical extravaganza. I’m working with Collaboraction, a Chicago theater group, to do this. They’re going to decorate their cavernous space to portray scenes from the book (the fantastical tropical metropolis of Eldritch City, the digestive system of the All-Devouring Mother goddess, the Dome of Doom where knights fight duels on flying armored ostriches, etc.).

Opening night will be a dance party where people dress up as gods and do battle-dancing in the Dome of Doom. My wife and I used to throw costumed battle-dancing parties back in the day; it’ll be like that, but on a much larger scale.

In the weeks after the costume party opening, we’ll bring in field trips from schools. They’ll browse the fan art galleries (which some of them may have contributed to), be wowed by the elaborately decorated environment we’ve created, take in some performances from the book, and participate in a writing workshop.

Hey, you! Reader of this interview! If you’ve read and liked Odd-Fish, and you’d like to do art based on it, your art can be featured in this gallery show in Chicago in the spring. The whole shebang will open in April. The deadline for submissions is March 15. Hoo-hah!

Finally: favorite mythical creature?

The Pooka. Not the legendary Irish demon of chaos. I mean the tomato-red balloon with yellow goggles from Dig Dug:

|

By the way, did you know they’re making a Dig Dug movie?! Check it out. The Internet doesn’t lie:

“So what’s in this for me?” “What do you want?” “Oh, the usual. Pineapples. Mushrooms.”

Thanks so much for interviewing me, Adam!

“Since this is the Dome of Doom, I decided to, well, turn it into

“Since this is the Dome of Doom, I decided to, well, turn it into