How To Make An AMAZING Movie for the 90-Second Newbery Film Festival (By Avoiding These Mistakes)

August 12, 2021

« Secrets of Story Episode 30: What Do We Really Mean By “Genre”? (with guest Jonathan Auxier) Secrets of Story Episode 31: How Does Irony Work In Stories? »

|

Right now is the best time to make your movie for the 90-Second Newbery Film Festival—our annual video contest in which kid filmmakers create short movies that tell the entire stories of Newbery-winning books in about 90 seconds. The weather is warm, which means it’s easier to shoot outdoors. And for many of us, school hasn’t started back up again, and this makes a perfect project to fill your empty summer days.

Now, making a 90-Second Newbery movie might be the first time you’ve made a movie at all. Good! I love that! I see so much amazing energy in those beginner efforts. Indeed, the very first movies I made feel like they have more lightning-in-a-bottle magic than more polished movies I made later. So: harness your amateur power!

“Yes, James,” you may say, “but I’m afraid of making the same embarrassing mistakes that most beginners make.”

I’M HERE TO HELP! In this post, I’ll outline the most common flubs, goofs, and blunders I see with 90-Second Newbery movies, and follow up with useful advice on how to avoid them. Keep these thoughts in mind when making your own 90-Second Newbery! (And of course, you can find even more help for beginning filmmakers on this part of the 90-Second Newbery website.)

This will be a long post, so buckle up your brain-flaps. I’ll break it into four sections: Advice For Behind The Camera, Advice For Actors, Advice For Screenwriters, and Advice For Non-Human Filmmaking.

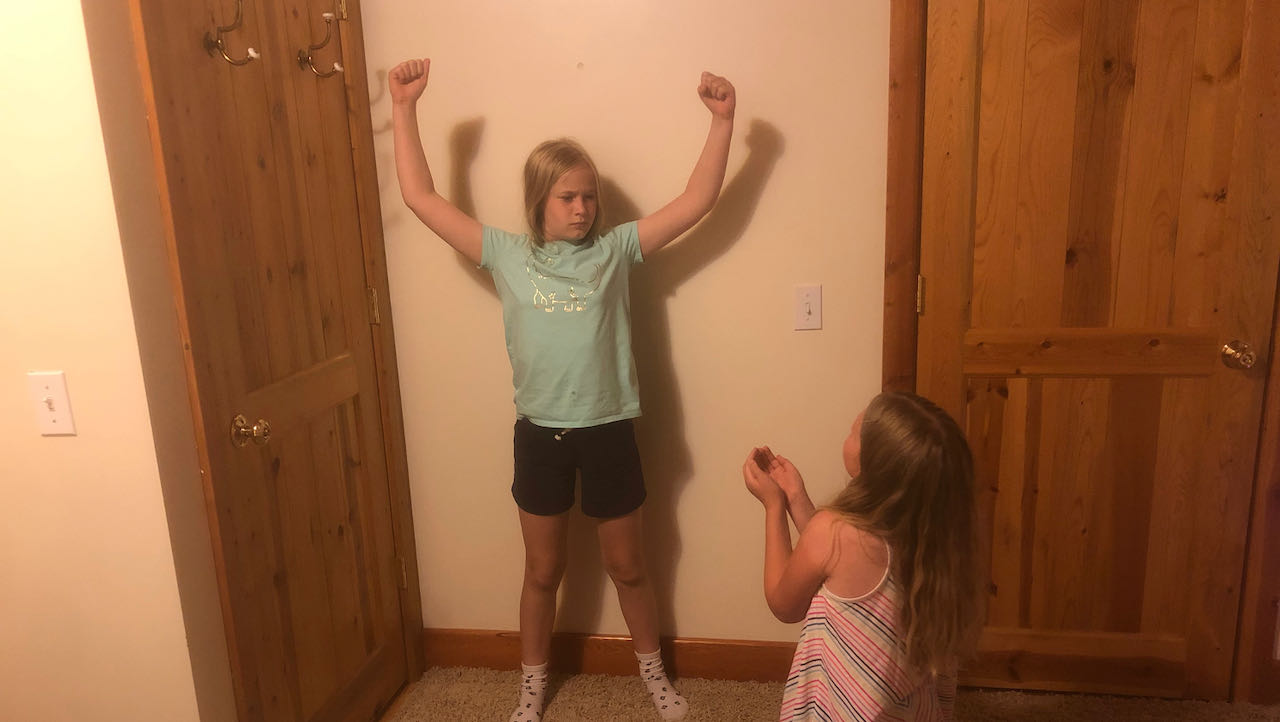

Thanks to my daughters Lucy and Ingrid for helping me with the example pictures!

Advice For Behind the Camera

1. You need a designated camera person. There must be someone in your group whose one and only job is to handle the camera and shoot the video. Don’t think you can just “set up” the camera in the corner or on the couch or whatever and then let it record the scene, unattended, while you act in front of it. I’ve seen this mistake too many times! Inevitably the shot is badly framed: somebody’s head will be cut off, or the actors will move out of the frame, or the only place where you can “set up” the camera is a place that gives a bad shot.

|

|

2. If you’re filming with your phone, don’t shoot in “portrait” mode. That is, when you’re shooting your 90-Second Newbery movie, you should hold your phone horizontally, in “landscape” mode. This is easy to forget because, for most purposes, we’re used to holding our phones vertically. And to be sure, when you’re shooting a video for, say, Instagram, it’s more appropriate to hold your phone vertically. But movies ain’t Instagram, baby! If you shoot in the dreaded “portrait” mode, there will be two big black bars of wasted space on either side of your movie when it’s on the cinema screen—not a pro look. Don’t be that person!

|

|

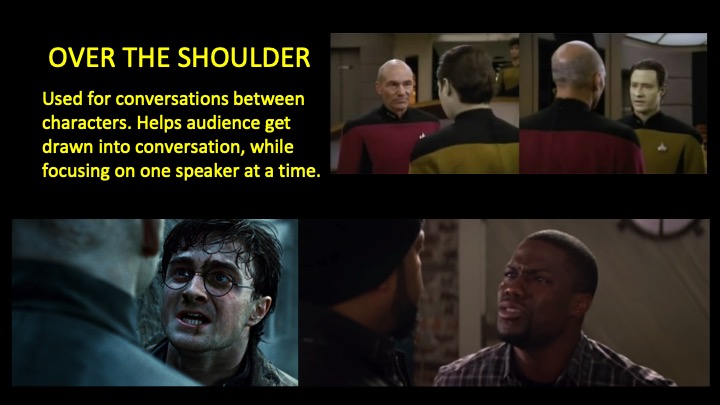

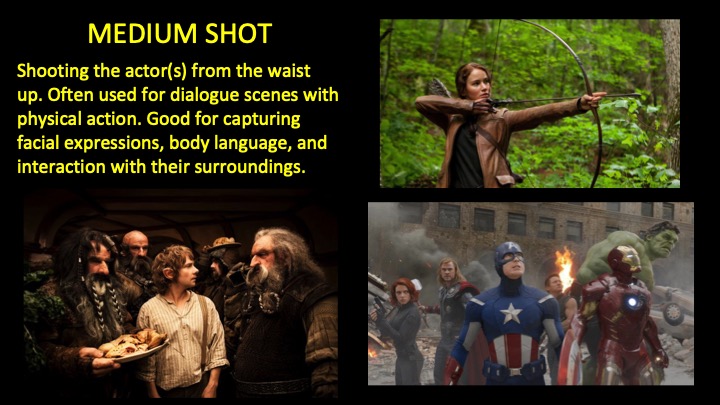

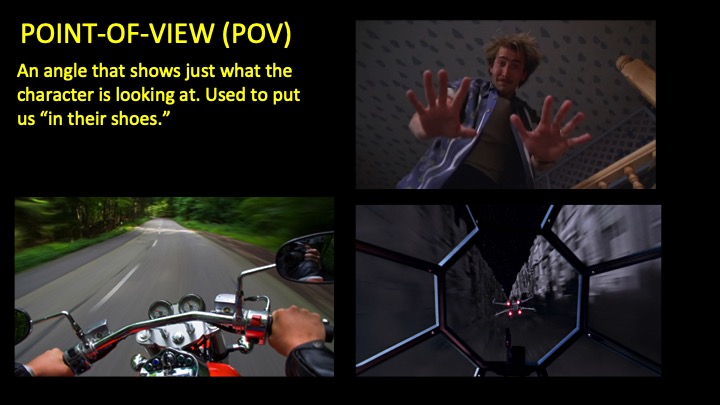

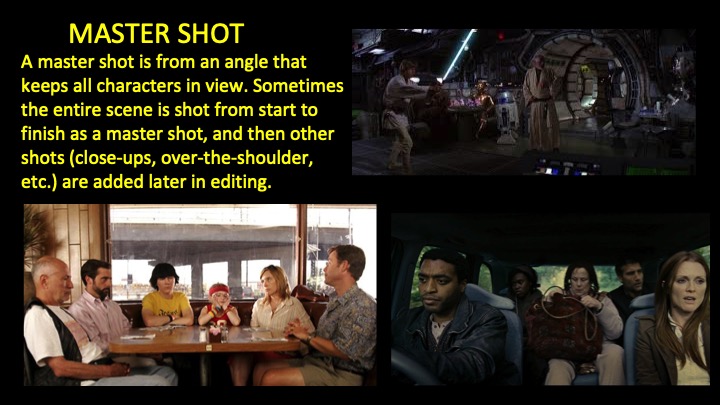

3. Use a variety of shots in your scenes. Don’t just have your actors perform the entire scene in front of stationary camera as though you’re merely recording a play. And definitely don’t just have your actors perform the scene without regard to where the camera is, while the camera person sloppily whips the camera back and forth to whomever’s speaking.

Most scenes should be composed of several distinct shots, composed and arranged for best effect. Check out this cinematography lesson that I put together (trust me, it takes just a few minutes and you’ll learn a lot). Then commit to using every single one of those shots I mention at least once in your movie—it will force you to be more creative with your camera choices, and will make a more interesting-to-watch movie.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Keep your actors’ faces visible and prominent. If the audience can’t see your actors’ faces, then they can’t see your characters’ emotions and we probably even won’t be able to hear them speak their lines. Don’t let someone’s head drift out of the shot, “decapitating” them. Don’t let someone turn their back to the camera. Don’t shoot a scene when people are too far away. The audience wants to see people’s faces! And if your actors are facing away from the camera while talking, it’s very difficult for the mic to pick up what they’re saying. Unless you have a good dramatic reason for it, keep everyone’s faces visible all the time. And push in to the actor’s faces for close ups! Don’t be afraid to let someone’s face fill the screen!

|

|

5. In a dialogue scene, cut back and forth between the speakers in separate shots. It’s usually really boring to watch a long unbroken shot of two people talking, like this:

|

Here’s a better way to shoot a dialogue scene: when one person is saying something, do a closeup on their face of them saying it—maybe over the shoulder of the other person. Then, when the other person responds, do an over-the-shoulder close up of their face. Alternate back and forth like that, and then edit those closeups together.

|

If you shoot your dialogue scene in this way, as a series of closeups or over-the-shoulder shots, then when you’re editing you can trim the pauses and dead space to make your scene snappier, and you can choose the best takes! You’ll also get better audio this way, since the mic will be closer to the speaker. This is especially important when you’re shooting outdoors and there is a lot more background noise.

6. Choose interesting locations to shoot in. Unless the scene actually happens there, don’t just shoot in a classroom or in your basement rec room or whatever. Shoot in a place that’s interesting to look at! Here’s a helpful tip: shooting outdoors in almost always more interesting than shooting indoors. (If you must shoot indoors, please don’t shoot with a white wall in the background. It’s boring to look at.)

|

|

So! If you’re making a movie of Hatchet, then try get to shoot it in the woods. If you’re adapting The Graveyard Book, try to shoot it in your local cemetery. If you’re making From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E Frankweiler, try shooting the museum scenes in an actual museum. And if possible, show off locations that are peculiar to your area! I receive movies from all over the country, and it’s genuinely interesting to see how Texas is different from California is different from New York City is different from Florida and so on. If your camera is stuck indoors, we don’t see that stuff. But that’s what will make your movie stand out!

7. Run your set like a pro. In many beginner’s movies, often there’s too much background distraction—chatter, odd noises, even random strangers wandering through the shot. How to fix this? By making it clear to everyone when you’re filming!

Before starting a shot, bellow “Quiet on the set!” to indicate to everyone they must be quiet while you film the scene. After you start recording, shout “Rolling!” to indicate that you have begun filming the scene. Then say “Action!” to start the scene itself. When you are done filming the scene, wait a few seconds, and then yell “Cut!”

All of these signals will help you in editing. If you can get your actors to start the scene a few seconds after you yell “Action!” and you say “Cut!” a few seconds after the scene is over, then you will have leeway to edit.

8. Film your scenes and shots multiple times, from multiple angles. If you shoot several takes of each line and/or action, or even from several angles, you will be thankful when you’re editing, because you’ll have lots of footage to work with. You can choose the takes with the best performances, with the best sound, with the best composition. It gives you choices!

9. Before you go out for a shoot, double-check that your phone/camera is charged and that there is enough memory on it. Shooting video takes a lot of power and memory. It would be a shame if you had gathered a big group of actors far away from any electrical outlet, and your filming was going great . . . and then your phone ran out of power! It might even be worth it to bring along an extra charger.

Advice For Actors

There’s a reason why professional actors are paid so much: it’s a serious job that takes a lot of skill and energy to do properly! But the great thing is, anyone can succeed at acting in a 90-Second Newbery, as long as you really commit. Here are some pointers:

1. Actually act! Don’t be embarrassed to go big. There’s nothing so boring to watch as unenthusiastic acting: mumbling, no emotion, looking like you don’t want to be there, looking like you don’t care. That is boring to watch! I can’t think of anything more “embarrassing” than being boring! So don’t be afraid to commit to a big, broad, loud performance, with lots of energy and humor and charm. Make the audience love you! Don’t mope around!

|

|

2. Actually know your lines. The most depressing thing to see in a 90-Second Newbery movie is when the actors are literally holding their scripts, reading their lines off of them. There’s no reason for this! You’re not doing a play, so you don’t need to “memorize” your lines. Most shots should be of only one or two lines at a time anyway (see point 5 in “Advice For Behind The Camera”)—if your shot is so long that it’s difficult to remember your lines, that probably means the shot is too long. Ditch the script!

3. Move around and do things. Here’s a weird but helpful tip: the audience should be able to understand what’s happening in the story even if the sound is off. That is, don’t rely entirely on the lines you’re speaking to get the idea across. If you’re threatening someone, grab them by the collar and shake them! If you’re expressing love or friendship, hug or shake hands! If you’re arguing, point your fingers, stomp, fold your arms, stalk away! Do physical actions that express how your character feels even if we can’t hear a word you’re saying!

Furthermore, conversations are more interesting to watch if the people are doing things. What’s more fun to watch: two people having a conversation while they’re sitting at a table doing nothing, or two people having a conversation while they’re fixing a car, or cooking dinner, or swinging on a swing set, or eating noodles with chopsticks? Move around, do things, perform tasks, interact with the environment around you, and your scenes will be much better!

|

|

4. Don’t look directly at the camera unless there’s a specific reason for it. In movies made by beginners, often the actor will say their line and then for some reason look directly at the camera, as if saying to the audience or director, “Uh, I’ve said my line? Is that OK?” Don’t do this! Of course, there are indeed some times you might want to look at the camera for comedic purposes, or to indicate dramatic intensity, or to do a meta thing. But unless you have a specific reason to do it, don’t look directly at the camera!

5. Speak clearly, and make sure your mouth is visible. Too often in amateur movies, the actor turns their back to the camera, or they are mumbling, and so the audience can’t hear a word they’re saying. Or the person speaking wanders offscreen entirely and delivers their line from there! Or everyone is screaming around them and the audience can’t understand what’s being said. Make sure your lines come across clearly.

6. Wear a costume! It’s so boring if everyone in your movie is just wearing their normal everyday T-shirt and jeans, or even worse, a school uniform. It’s not fun to watch, and it’s confusing—especially if you’re playing a different age, gender, or species. Anyway, costumes are fun!

How is the audience supposed to believe your character is, say, a “policeman” if they don’t at least have a badge? Or a “cowboy” if they don’t have a cowboy hat? Or a “pig” if they’re not dressed like a pig? Costumes are an opportunity to get a lot of story information across quickly and visually. Since your movie must be short, every character must be identifiable the moment the audience sees them.

This is particularly crucial if an actor plays multiple roles. In your movie of Holes, how are we supposed to realize that the same actor is playing both the Warden and Kissin’ Kate if the actor is wearing the same clothes in both scenes?

|

|

7. Use props! Are you indeed making a movie of Holes? Then show me people actually physically digging holes in the ground with shovels.

Are you adapting a story that has swordfights in it, like The Black Cauldron? Get fake swords and give the audience a fun-to-watch choreographed fight scene!

Does your movie have a scene where people are eating? Then actually eat food. I’ve seen so many 90-Second Newberys with bizarre eating scenes in which the actors dip spoons into empty bowls and pretend to eat . . . nothing! Insane! I’ve also seen movies in which people knock on invisible doors, talk on invisible phones, and throw invisible balls.

This isn’t improv, people! Get the prop!

|

|

Indeed, you can go beyond props. Are you adapting Dead End in Norvelt, whose main character frequently has nosebleeds? Show me blood spurting from his nose!

Are you adapting El Deafo or Hatchet? Both books have great vomiting scenes—go for it, show me the vomit!

Are you adapting Ramona Quimby, Age 8, in which Ramona cracks a raw egg onto her head? CRACK A REAL RAW EGG ON YOUR HEAD AND THE AUDIENCE WILL LOVE YOU FOREVER.

8. Make sure your dialogue is short and to the point. You should never have meandering dialogue that goes something like, “Well, you know, as I always said, you gotta go, well, actually what I meant is . . . ” blah blah blah. Make your point quickly and get on to the next point quickly—remember, these movies are supposed to be short!

Advice For The Screenwriter

Most of the advice from above also applies to scriptwriting. (Your lines should be concise! Use props and physical actions! Find good locations!). But here is some additional advice that is particular to screenwriting 90-Second Newberys:

1. Give your story a cool twist that will make it fun to watch. That is, don’t just do a straightforward adaptation of the book. Find some twist on the story that will make it interesting—like making it in an unexpected genre, or in the style of a well-known movie.

Sure, you could make a straightforward adaptation of Charlotte’s Web . . . but it’s much more interesting to make Charlotte’s Web in the style of a horror movie.

The Whipping Boy is a standard medieval tale, and I guess you could make it in that style, but isn’t it more interesting to make The Whipping Boy in the style of Star Wars?

And a book like The Tale of Despereaux is your run-of-the-mill talking animal story, but what if you adapted The Tale of Despereaux in the style of the musical Les Miserables?

Once you decide a cool twist like this, that will naturally lead to all kinds of jokes and scene ideas that will make your movie so much more fun to watch.

2. Make a true dramatization of the book, not a mere trailer! The trailer format rarely works. Most of the time, it’s just a bunch of disconnected scenes that serve to advertise the story, but not really tell the story. That’s unsatisfying.

Please don’t make your project using the “trailer” template that comes with iMovie. First of all, half the creative work is done for you—you’re just slotting your footage into iMovie’s “trailer” template. Furthermore, that iMovie template doesn’t allow you to put any spoken dialogue into the trailer, because it just lays preset music over everything. In the end, you’re forced to do the “storytelling” entirely with on-screen text. Leave the templates behind, and dare to do your own thing!

3. Have the characters say names early and often, and make their relationships to each other immediately clear. So many times, I’ve been watching a 90-Second Newbery movie that starts with a bunch of uncostumed actors standing around, saying lines to each other, but I don’t know who anybody is, what their relationship to each other is . . . or even who the main character is!

Make it clear as early as possible who the main character is, and what that character’s name is. When they interact with someone else, make it immediately clear what their relationship is. You have only 90 seconds, maybe four minutes max, to introduce a bunch of characters and tell their whole story in a way that is both entertaining and NOT CONFUSING. If we don’t know anybody’s name, it becomes much more confusing! Get those names out and relationships out there immediately!

Advice For Non-Human Filmmaking

As soon as you are doing a movie that isn’t live-action, you’re already working at a disadvantage. Now, don’t get me wrong: I’ve seen many great 90-Second Newberys without humans onscreen. Movies that are animated, or puppet shows, or stop motion. BUT . . . it takes a lot of work to make those succeed!

On the other hand, the cheapest and most effective special effect is the human face. People like to look at people! Humans enjoy seeing human faces, they enjoy hearing human voices, and they enjoy watching human bodies! This is a great advantage for you, because you and your friends possess human faces, human voices, and human bodies (presumably). Use them!

But let’s say you’re dead set on making a movie that has no humans in it. Then please take my advice:

1. Don’t submit something that is basically a PowerPoint presentation. Guys, I gotta be honest. At this point I’ve watched literally thousands of 90-Second Newbery movies. And every year I get dozens of “movies” that aren’t really movies at all—instead, they’re just a series of stock photos (that is, the filmmakers didn’t even draw the pictures or shoot the photos themselves) with onscreen captions explaining the plot. Like this:

|

Maybe there’s some music in the background. But that’s it! There often isn’t even a human voice! Admit it: you wouldn’t voluntarily watch something so brain-meltingly boring.

When you’re making your 90-Second Newbery movie, your goal should be to make something that is so good that even a stranger would enjoy it. That means your movie can’t just be a minimal “trailer” that barely explains the story. A 90-Second Newbery movie should be a full-on dramatization of the story, hopefully with human actors, with spoken dialogue, that expresses the entire plot of the book.

I get it: maybe your teacher assigned you to make a 90-Second Newbery, you don’t want to do it, and you want to get through the assignment with minimum effort. Fine! You can submit that boring garbage to your teacher. But don’t submit it to me.

2. Don’t make a movie with Powtoon or Gacha. These movies almost never turn out well. Why? Because it’s just a bunch of two-dimensional drawings that you didn’t even draw standing around in front of a flat premade background, with occasional dialogue balloons popping up.

|

|

Why give up your creativity to an app that makes your movie look the same as every other movie on their platform?

Another problem: there’s very little movement in Powtoon or Gacha movies. But they’re called movies for a reason! Remember, the most interesting thing in the world to watch are REAL HUMANS DOING THINGS. Not just standing around talking.

Now, occasionally I do receive good movies made in other digital platforms, like Minecraft. Here’s a great one based on Wanda Gag’s 1928 Honor Book Millions of Cats:

But even many Minecraft movies have a similar problem: unless they’re done as skillfully as the one above, it just looks like we’re watching someone play a video game—with no cuts, dialogue, or real cinematography—while someone just mumbles the plot of a book over it. Not fun!

All this advice also applies for movies made in Scratch. It’s possible to make a good movie in Scratch, but only if you use your own original art (not the default sprites!) and animate it in interesting ways.

3. There’s nothing worse than a bad puppet show. You want to make your 90-Second Newbery as a puppet show? Great! Learn from the best—here’s a fantastic version of Arnold Lobel’s 1973 Honor Book Frog and Toad Together done as a puppet show:

Why is this movie so good, beyond the great script and performances? I’ll tell you why:

(1) Because the puppets are charmingly made.

(2) Because the puppets move around an interesting three-dimensional environment.

(3) Because the puppets do physically interesting things (drinking tea, jumping around, running from an avalanche, squeezing through a door).

(4) Because there are many camera angles and edits.

That’s what makes a great puppet-based 90-Second Newbery! But unfortunately I often get submissions of puppet shows that don’t do any of this.

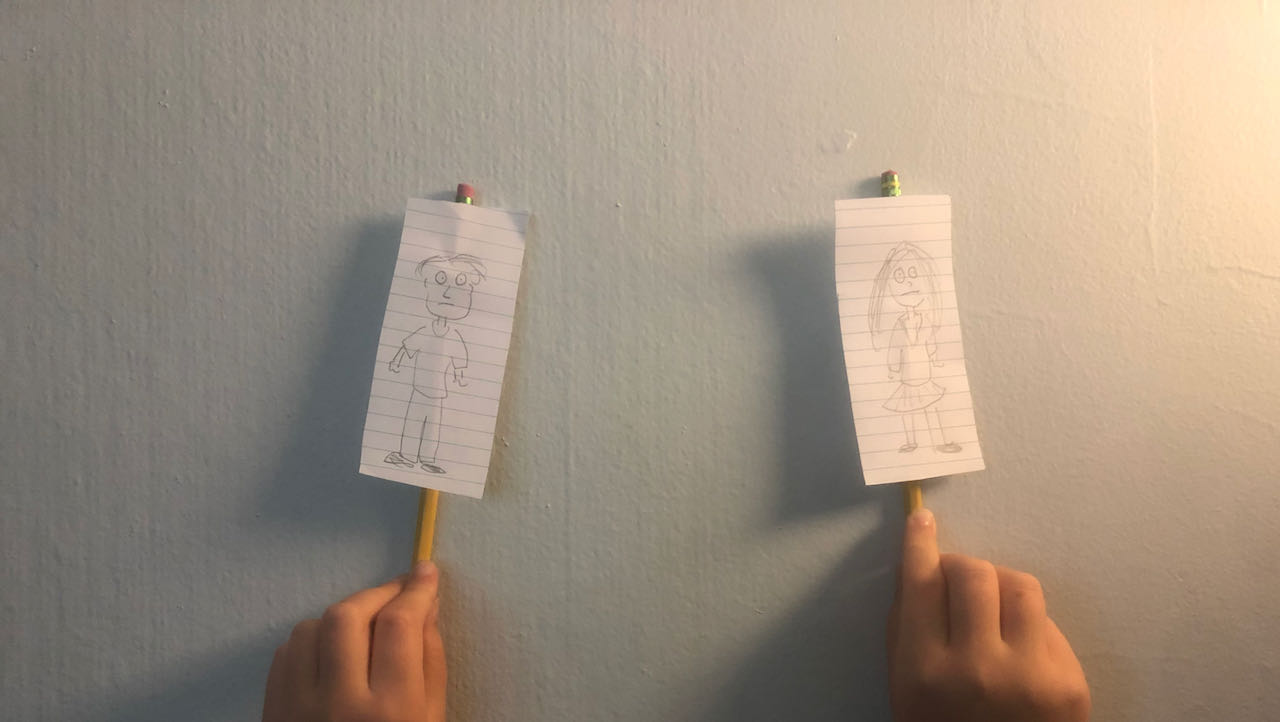

For instance, sometimes I see submissions in which the “puppets” are just cut-out strips of looseleaf paper, carelessly drawn on in pencil (not even in color!), taped to rulers or pencils or popsicle sticks. No craft.

|

Such puppets can’t do any interesting physical movement. They just flop around lifelessly. The most that happens is that the puppeteer shakes the puppet to indicate that it’s “talking.” Not interesting to watch. Remember, puppets can do things humans can’t do—take advantage of that!

Even worse, there is often no real environment for the puppets to be in—just a blank wall or hastily-drawn background. (Shooting your puppet show outside is usually more interesting to watch than inside.)

Worst of all, in many of these puppet shows, the camera doesn’t move at all! It just stays still and the puppets “do a show” in front of it. That’s not even remotely interesting to watch! Remember, you’re making a movie, not merely recording a play onstage. Do a variety of camera angles and cuts. (You can learn a lot from my crash course in cinematography.)

By the way, in a puppet show, unless you have a puppet whose mouth actually moves, it’s particularly difficult to tell which puppet is “talking.” Instead of just shaking the puppet to indicate it’s talking, solve this problem by doing a closeup on the speaking puppet’s face. (I recommend recording all the puppet movements first, and then dub in the actual dialogue, music, and sound effects later in editing.)

To sum up: there’s nothing wrong with puppet shows. But you gotta put some effort into it. When they’re great, they’re the best. When they’re bad, they’re awful.

Summing Up

Making a movie is hard. Making your first movie is harder still. You won’t get everything right, and that’s okay! Maybe you’ve made some of the mistakes I’ve listed here in your current movie and you feel a bit shy about it. Or maybe you’ve made some of these mistakes in your previous 90-Second Newbery movies and now you feel embarrassed.

Don’t be! Making a movie isn’t like doing a math worksheet. It’s not about getting a “right” answer. Why, it may even be that your movie made all the “mistakes” I’ve listed above . . . and yet somehow, by the force of your art, it’s actually a fantastic movie! Then that’s great!

The important thing to remember is that your movie won’t be perfect. It’s always going to be a weird tug-of-war between your vision, your capabilities, and your resources. But hopefully these tips will help you make a better movie, and avoid some of the more obvious missteps I’ve seen.

In the end, all my advice comes down to these two questions:

- Would your movie be fun to watch even for people who aren’t you and your friends?

- Would your audience understand the story even if they haven’t read the book?

If you feel confident answering “yes” to both questions, then you’re golden! In the end, I want you to submit movies that you can feel proud of.

Now get cracking! The deadline is January 14, 2022! If you need more help, check out our video resources page here, which features a detailed step-by-step how-to guide on “How To Make a 90-Second Newbery” along with help on free soundtrack music, green screen, special effects, and more!